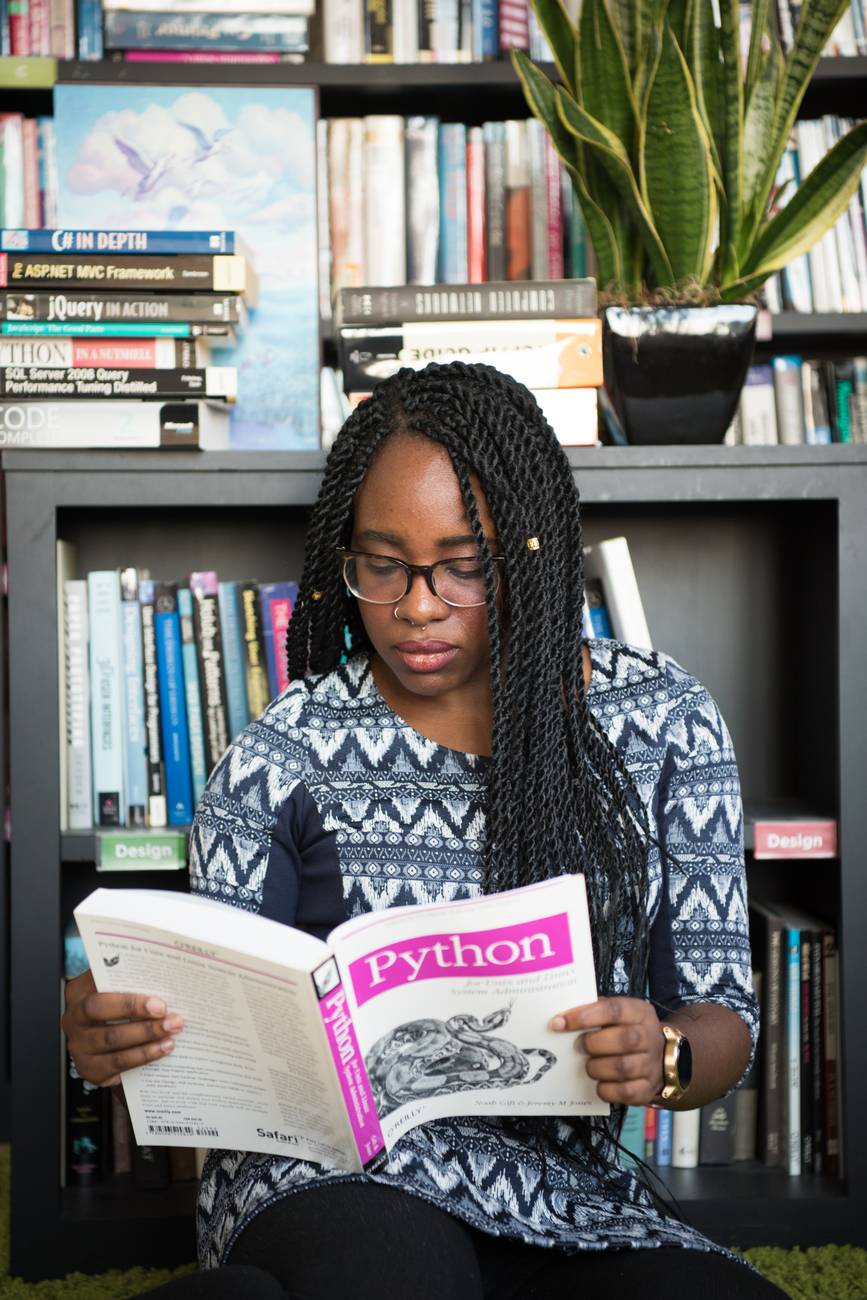

Featured image from: Digital Evolution of Schooling

Inquiry Blog 3

| Glossary of Acronyms |

| ICT: Information and Communications Technology |

| MOOCs: Massive Open Online Courses |

| NOOCs: Nano-MOOCs |

| PD or Pro-D: Professional Development |

| SMART goals: Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, Time-based |

| SWOT: Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats |

| T-L: Teacher-Librarian |

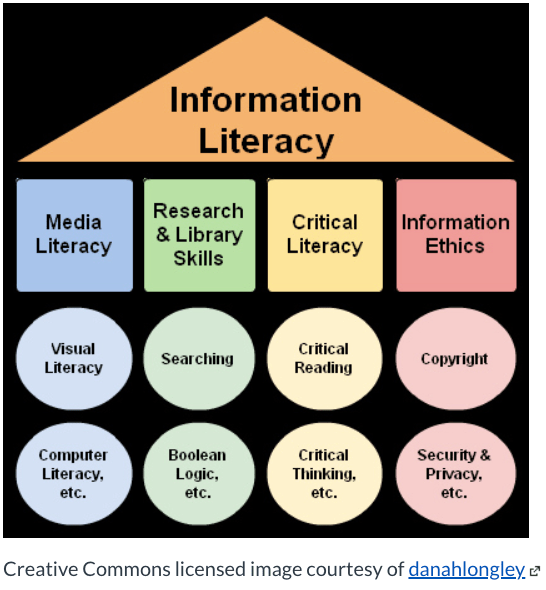

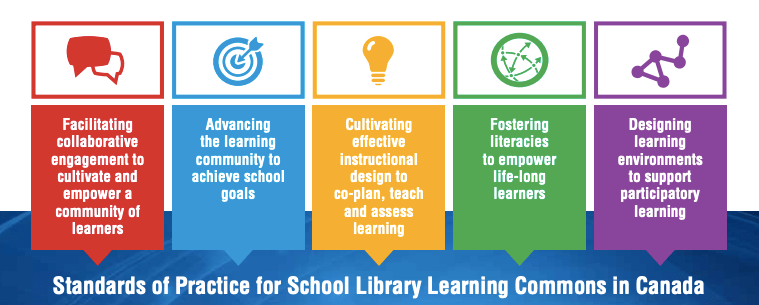

One of the things that drew me to the teacher-librarian diploma was the opportunity to be a leader in the school. When I tell people that, sometimes they give me a quizzical look and ask “In what ways do you mean a leader?” I think that there is a misconception around the role of the teacher-librarian, and sometimes an underestimation of the library as central to curriculum development, literacy, and digital literacy.

I have great role models in our school – teacher-librarians who make the library a gathering place for both staff and students; offering guidance and support in development of projects; hosting staff meetings and other district functions; providing space to showcase student work, among myriad other things that make the library a bustling, comfortable place for everyone in the building. The teacher-librarians provide instruction to students almost every block of the day, and are available to guide and teach one-on-one, which is especially great when you are used to being pulled in so many directions as a teacher of 30 students.

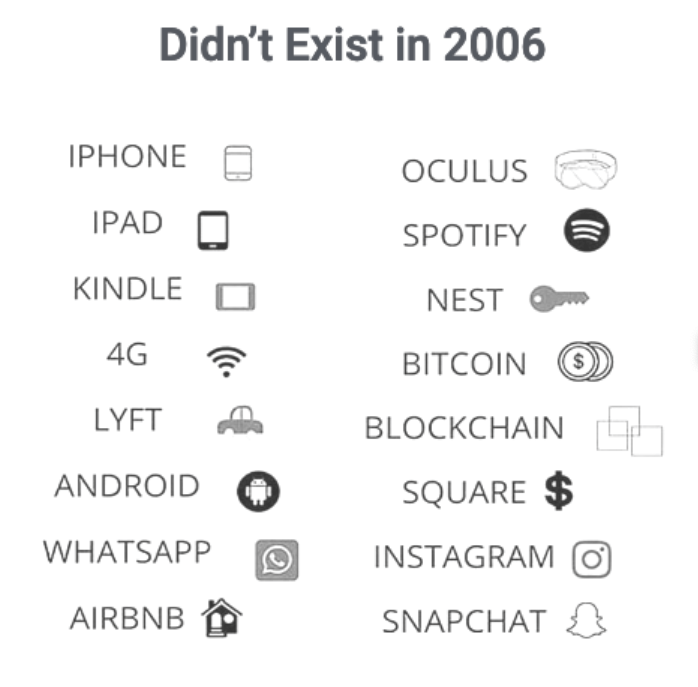

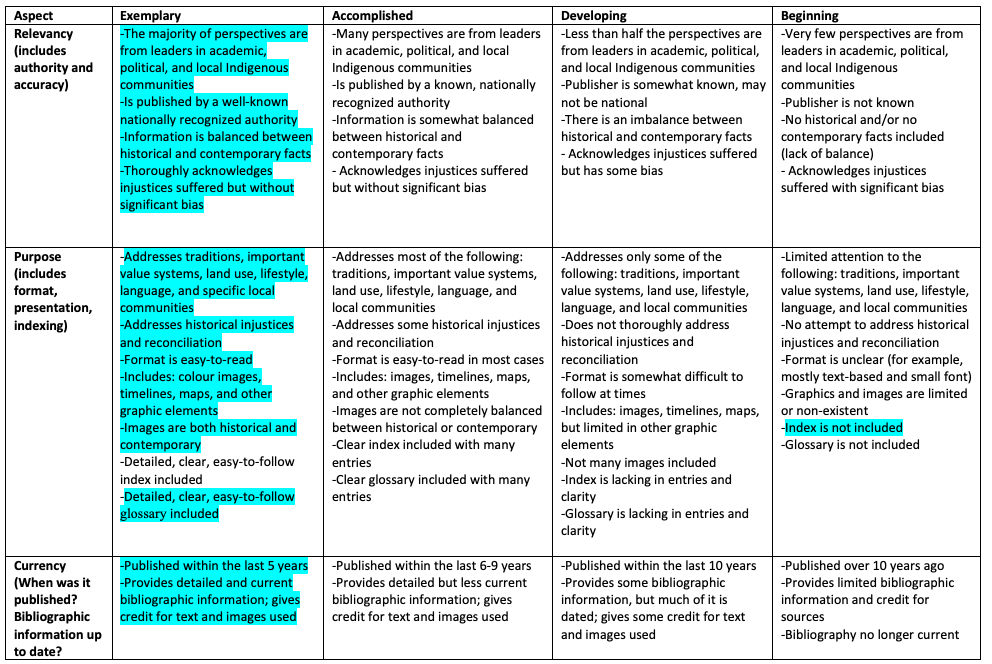

In my previous blog, I discussed how lifelong learning was an important part of professional development, particularly in terms of ICT. I talked about some strategies and goals on how to improve my own digital literacy practice, but now it’s time to turn outward and imagine how I would facilitate professional development in ICT for other educators in the school and/or district in my role as a teacher-librarian.

EBSCO published a white paper in 2017 titled “Advocacy and the 21st Century School Librarian: Challenges and Best Practices”. It discusses the teacher-librarian (T-L) leadership position, stating that “[…]mentorship involves more than simply showing teachers how to use the library’s online catalog and subscription databases. School librarians can empower teachers to develop proficiency with various technologies so that they may become more confident and independent (Perez, 2013, p. 23)” (5). The T-L becomes the facilitator of professional development, in both formal and informal ways, always keeping in mind that the T-L is primarily a listener, who solves problems with patience and kindness. In order to be a leader of any type, you must make others feel welcome and heard, and feel that no (tech) issue is too small or insignificant to solve.

Kristin Daniels, an educational technology consultant in the U.S., found that the workshops she facilitated for teachers were great in concept, with positive on-the-spot feedback from teachers, but were not great in practice. In other words, the learning done in those workshops wasn’t translating into useful classroom strategies. She explains in her TEDx talk “Empowering the teacher technophobe” that giving teachers release time to work one-on-one with her, solving technical issues together, had long-lasting, impactful results.

Connecting with them on a monthly basis, Daniels was able to individualize her mentorship for these teachers, finding “a successful project that was just right for one teacher’s tech skill[s]”; providing “a little bit more information about a tool that [another teacher] was already familiar with”; and helping a teacher who “didn’t need tech information [but] needed help designing the project, and then we provided her with the resources and support to get it done” (Daniels). These more informal one-on-one discussions occur regularly between staff and T-Ls at our school, with similar results to Daniels, who found that this type of PD had far-reaching positive consequences for students and teachers. However, teachers at our school typically use their lunch or prep time for this type of professional learning, and only if they are inclined to ask for help. Many teachers feel too stretched for time to try new digital strategies, preferring what they are comfortable with. Professional learning from teacher-librarians might be more widely used by staff if it was offered in a more formal way, such as release time for one-on-one instruction.

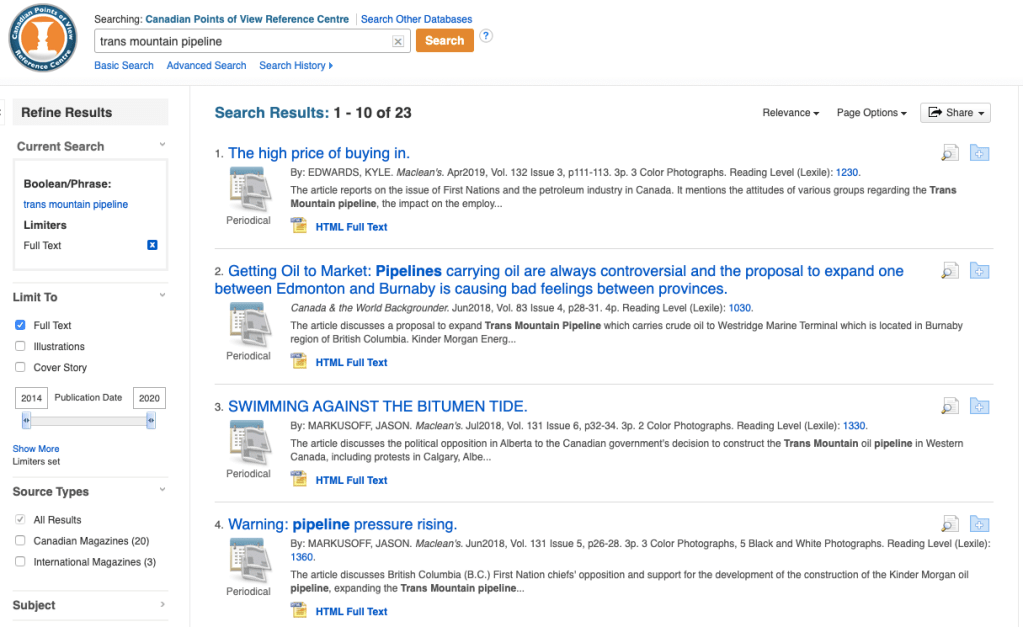

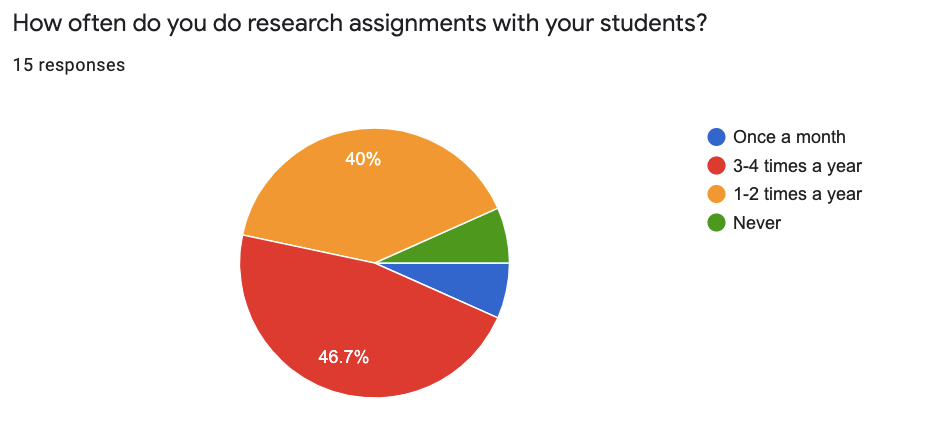

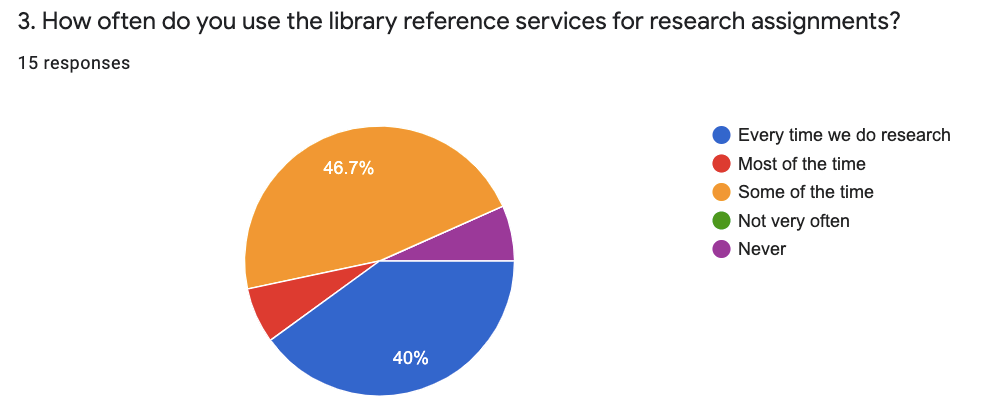

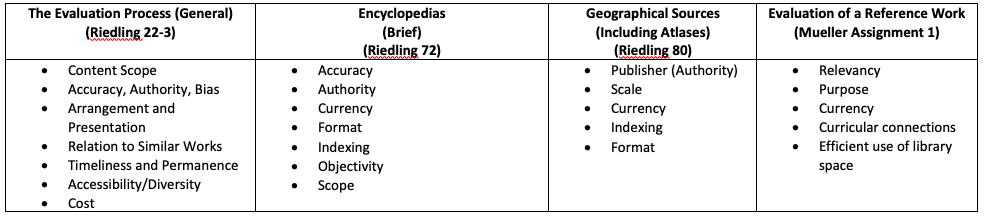

Yet, release time is expensive and some districts may not have the funding to allow this. A few ways to get around this are district or school-wide pro-D days, lunch-and-learns, or professional learning outside of school hours, which often takes place online. In terms of providing ICT workshops for larger groups, we can think of it as collaboration between staff and the T-Ls. Debra E. Kachel’s article “Advocating for Collaboration” examines a seven-part plan to improve collaboration in this way. Her first suggestion is to “Define the issue”, which is an obvious first step, but one that can sometimes be done poorly. One simple and effective way to conduct a survey on ICT deficiencies is through Google Forms. In our district, we use G-suite for education, so staff are familiar with the platform. Conducting a survey at the beginning of each school year or term to check in on where more ICT education is needed would be a great tool to guide professional development.

| Debra E. Kachel’s Seven-part Plan when “Advocating for Collaboration” |

| 1. Define the issue. |

| 2. Find supporting research and facts. |

| 3. Articulate goals. |

| 4. Identify allies, opponents and undecided. |

| 5. Design the campaign. |

| 6. Develop a communications plan. |

| 7. Implement and assess. |

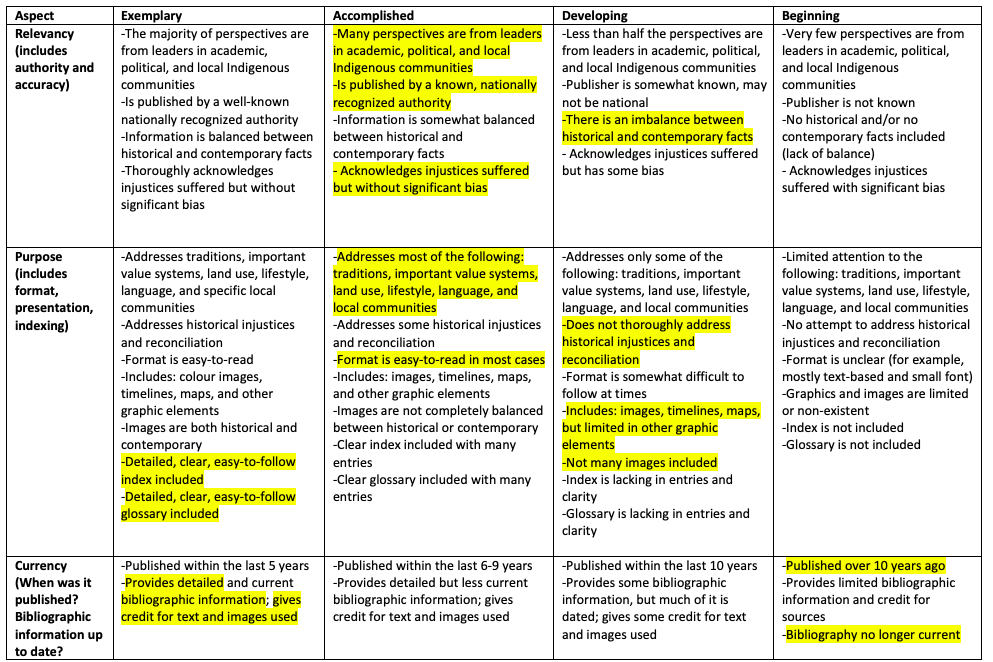

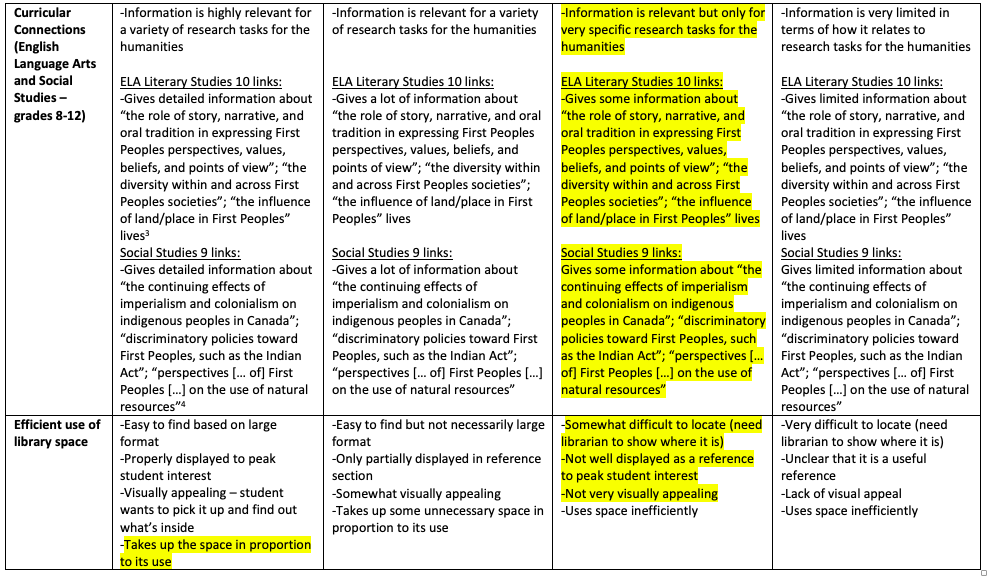

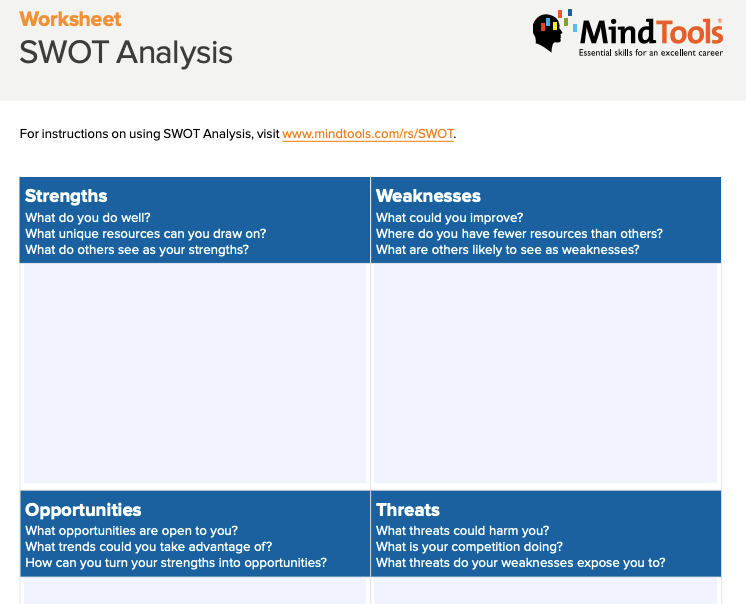

Furthermore, Kachel suggests using SWOT analysis, which stands for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats. She says “An environmental scan of the school is […] needed to see the bigger picture and identify potential inroads to improve collaboration” (48). (You can find a downloadable SWOT matrix worksheet on MindTools). Identifying SWOT in digital learning, for both the individual and the group, can establish professional development outcomes, as well as capitalize on staff members who already have the skills and knowledge you may lack. Providing some time at staff meetings where teachers can reflect on ICT use in their classrooms will hopefully lead to collaboration outside of that time.

Kachel notes many benefits of collaboration, including that it:

- Shares planning, teaching, and assessment of student work among teachers and librarians

- Stimulates new and creative ideas resulting in improved teaching and learning

- Increases use of library and curated resources (49)

In all three cases, you can see how collaborating on ICT will improve staff and student outcomes. The library is a natural place to use ICT, since the teacher-librarian is knowledgeable on contemporary digital technologies, and can provide the one-on-one guidance on which staff and students thrive.

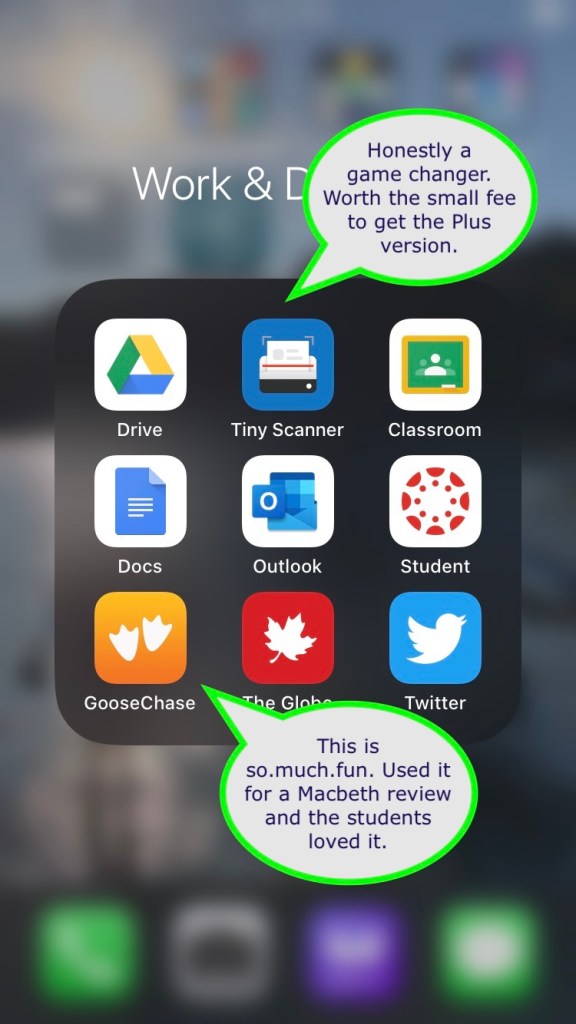

In addition to formal pro-D, the teacher-librarian can provide tech support through informative emails or by creating Screencasts that quickly teach digital skills. Creating a weblink on your library home page for staff, where you can upload tech resources, would be a good way to centralize that information. The inclination is sometimes to do a Google search to find the answer to your tech problems; and although this can prove successful, vetting good YouTube videos to solve common tech problems could be helpful for staff. Personally, while learning for this course, I went back to an email with a link to a Screencast made by my teacher-librarian that outlined how to access and use NoodleTools so I could properly cite a complex journal article. It was an easy solution from a professional, who had the right tech info at the right time.

As noted by Castaño-Muñoz et al., “The use of information and communication technology (ICT) as a tool for responding to the challenges [of teaching] is one of the most sought-after topics regarding teacher training needs” (608). So we know that professional development is ongoing and significant when it comes to ICT, but there is often not enough time set aside for it. Therefore, if the T-L is going to be involved in facilitating pro-d workshops, it’s important for them to be done well. Discovering the areas of need through surveys or SWOT is the first step, but one must also create a comfortable space for learning and collaboration, where teachers feel that their opinions and time are valued. Elena Aguilar, who wrote “10 Tips for Delivering Awesome Professional Development”, explains that “[…] often […] the presenter talks a lot and the participants walk away feeling overwhelmed and a bit frustrated”. I know I have definitely felt that way during professional development. And as teachers we should know better than to have people sit passively for more than 15 minutes without participating!

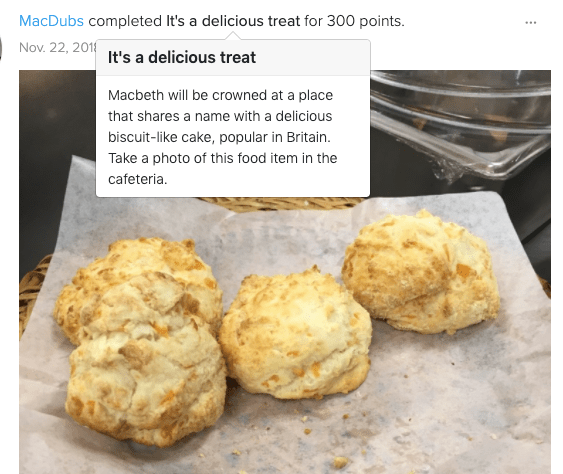

In your planning consider how you will balance information with practice so that “[p]articipants [can] walk away feeling that they learned something new and they can actually do something differently when they return to class tomorrow” (Aguilar). Having teachers make concrete connections to their classroom learning, and also keeping them accountable can help. Perhaps you have them write SMART goals for their own ICT learning; perhaps you have monthly check-ins like Kristin Daniels to see where they are progressing or lacking, and if they would like more one-on-one guidance. Partnering with another teacher can also lead to more accountability; planning a collaborative lesson or assignment with ICT use can be very rewarding. Finally, as the T-L you could organize and host a “Digital Tech Week” or month in the library, where teachers and students share the positives and negatives of using new technology in their learning.

One last area that can promote digital literacy for teaching staff is MOOCs, or Massive Open Online Courses that are free of charge or have a minimal fee. There is no limit on the number of participants, and you can complete them on your own time, which makes them appealing. Will Richardson believes that MOOCs show “a real shift in the way we define and acquire an ‘education’” (Loc 111), noting that the highest reputed Princeton, Stanford, and MIT are all involved in facilitating MOOCs.

In the article “Who is taking MOOCs for teachers’ professional development on the use of ICT? A cross-sectional study from Spain”, Castaño-Muñoz et al. note that “Recently, several Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) on teaching skills have been added to this range of possibilities offering flexibility and more training possibilities to teachers” (608). They conducted a complex survey of educators using this online learning for professional development, and the MOOCs included: “how to implement digital gamification in the classroom for enhancing students’ motivation” and “how to foster cooperative learning through digital technologies” (610). They also used Nano-MOOCS or “NOOCs [that] were oriented to develop teachers’ general digital competencies” (610). Using the information from initial surveys on where teachers need support for ICT, the teacher-librarian could work with the digital specialist in the school or district, and help facilitate where and when to find MOOCs and NOOCs to support individual learning. Some MOOCs offer certificates (for a small fee), while digital “badges” can be made available as incentive to complete the online courses.

In the end, the teacher-librarian is a facilitator who brings knowledge, shares knowledge, and guides others towards knowledge. And since ICT is such a significant part of teacher (and life) success, that knowledge must also be facilitated by the teacher-librarian. So don’t hesitate to seek out answers to your technological questions from your own teacher-librarian or from other T-Ls online!

Works Cited

Aguilar, Elena. “10 Tips for Delivering Awesome Professional Development.” Edutopia, George Lucas Educational Foundation, 18 Sept. 2014, http://www.edutopia.org/blog/10-tips-delivering-awesome-professional-development-elena-aguilar. Accessed 2 Aug. 2020.

Castaño-Muñoz, Jonatan, et al. “Who is taking MOOCs for teachers’ professional development on the use of ICT? A cross-sectional study from Spain, Technology, Pedagogy and Education.” Technology, Pedagogy and Education, vol. 27, no. 5, 2018, pp. 607-24, DOI:10.1080/1475939X.2018.1528997. Accessed 2 Aug. 2020.

Daniels, Kristin. “Empowering the teacher technophobe: Kristin Daniels at TEDxBurnsvilleED.” YouTube, uploaded by TEDx Talks, 6 Nov. 2013, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=puiNcIFJTCU. Accessed 2 Aug. 2020.

EBSCO, compiler. Advocacy and the 21st Century School Librarian: Challenges and Best Practices. EBSCO, 2017. Ebscohost.com, http://www.ebscohost.com/assets-whitepapers/Advocacy_and_the_21st_Century_School_Librarian-EBSCO-Whitepaper.pdf?_ga=2.18133497.1736181280.1513717168-1955623741.1513717168. Accessed 2 Aug. 2020.

Kachel, Debra E. “Advocating for Collaboration.” Teacher Librarian, vol. 46, no. 4, Apr. 2019, pp. 48-51, antiochlis.libguides.com/ld.php?content_id=49265318. Accessed 2 Aug. 2020.

Richardson, Will. Why School?: How Education Must Change When Learning and Information Are Everywhere. Kindle ed., 2012.