This course has offered many opportunities for learning and growth as an educator and teacher-librarian hopeful. The key learnings for me can be explored with the answers to these three questions:

- How can libraries help students become critical thinkers?

- How can libraries help students be themselves?

- How can libraries help students succeed in all areas of learning?

These are similar to Hillary Clinton’s three reasons why we need libraries more than ever, from her speech to the ALA in 2017:

- Reading changes lives

- Libraries create community for diverse populations

- We need critical thinkers more than ever

How can libraries help students become critical thinkers?

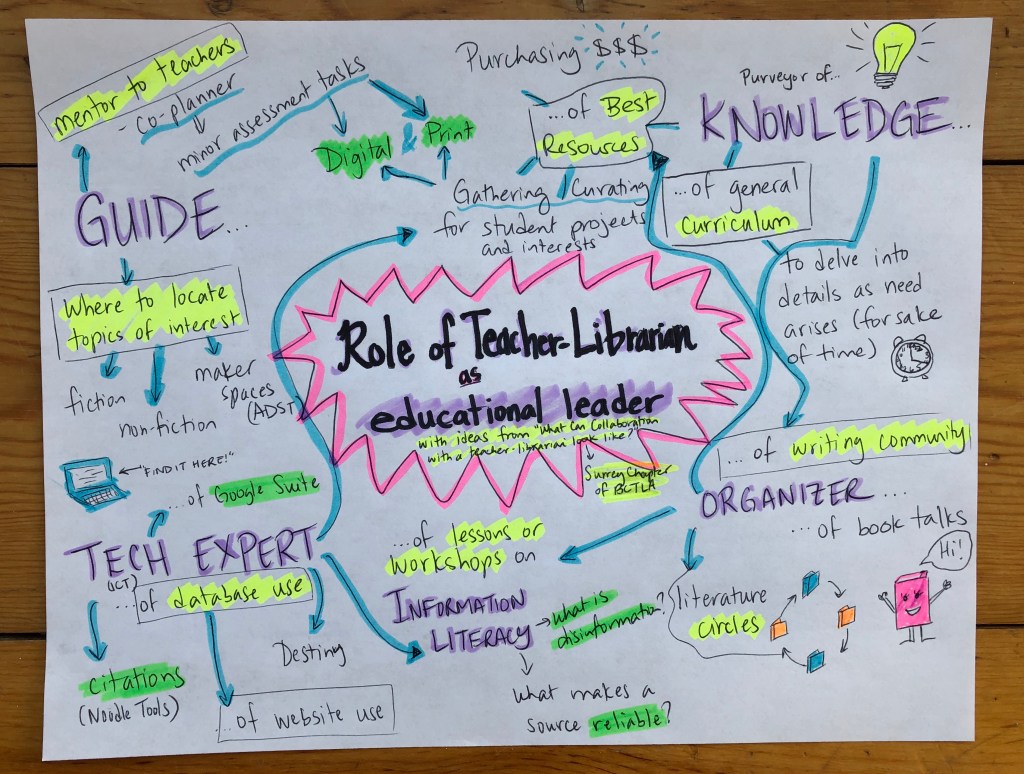

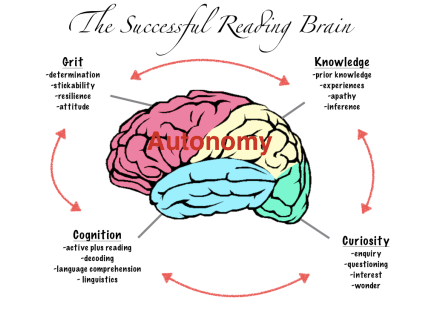

One of the biggest challenges facing youth, and society as a whole, is the massive amount of information available online. This course has highlighted the role of teacher-librarian as a leader in analyzing digital data, as someone who helps guide students toward reliable sources and various perspectives. Kimberly Lenters examines how graphic novels as multimodal texts support critical literacy for students: “They learn to decode and encode information, their comprehension of often complex ideas is aided by the use of multiple sign systems, they learn about different ways information and story may be conveyed for different audiences, and they have the opportunity to critically engage with important topics” (645). These are media-analysis skills that can be applied to all texts, multimodal or not, both online and in the classroom.

In fact, Lenters highlights the need for multimodal text analysis given “recent discussions in the media regarding fake news and consumer fraud” and that “people of all ages encounter a plethora of information, ideas, and invitations in the digital spaces in which they participate (e.g. websites, Facebook, Instagram)” (645-6). This was also discussed by Hillary Clinton in her address to the American Library Association: “As librarians […], you have to be on the front lines of one of the most important fights we have ever faced in the history of our country – the fight to defend truth and reason, evidence and facts”. Clinton says this in light of the disinformation spread not only during the 2016 election campaign, but also the corruption of news media that continued afterwards. Three years on from her speech, this is only more obvious a problem, as one of the most influential leaders of the free world continually aims to discredit reliable news sources.

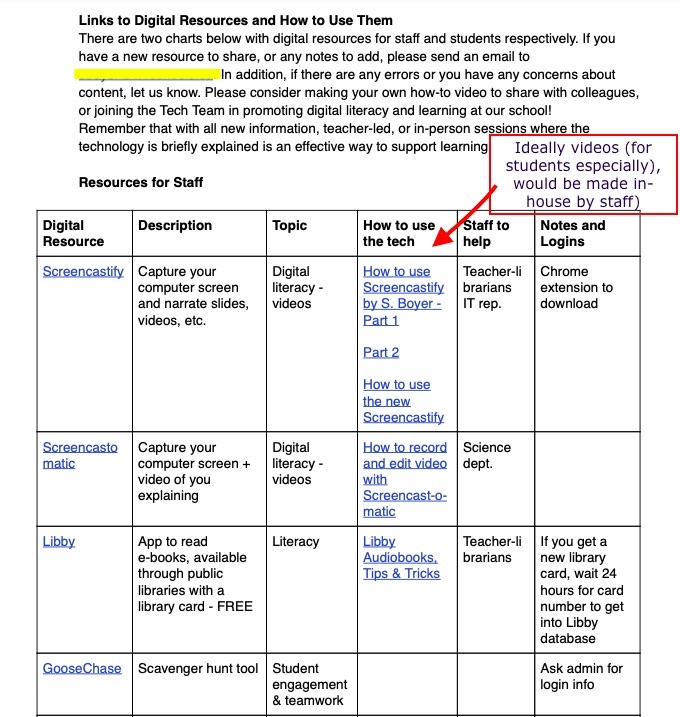

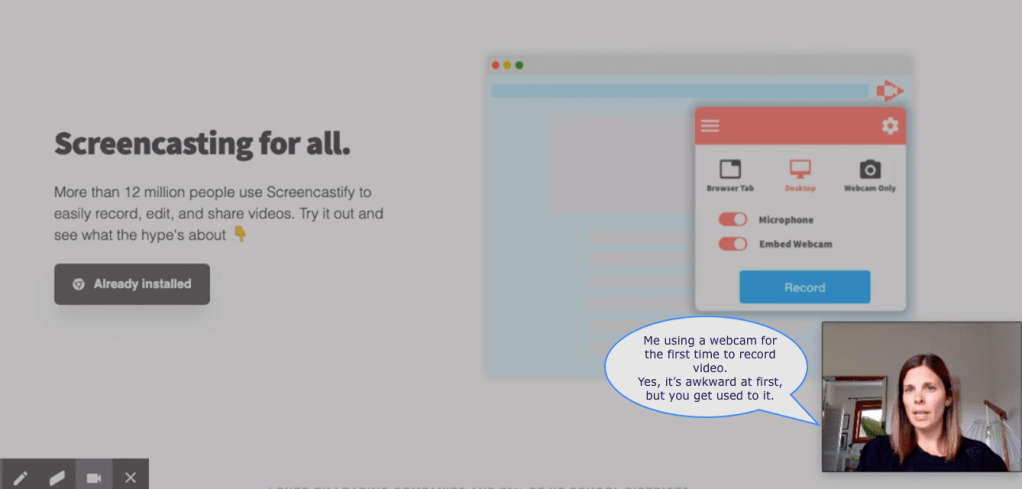

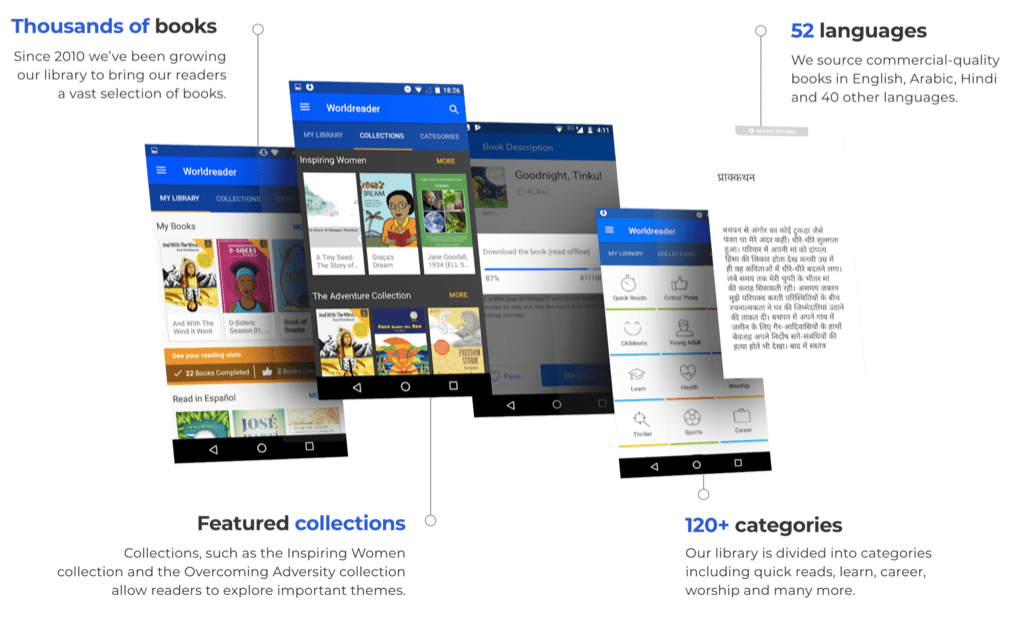

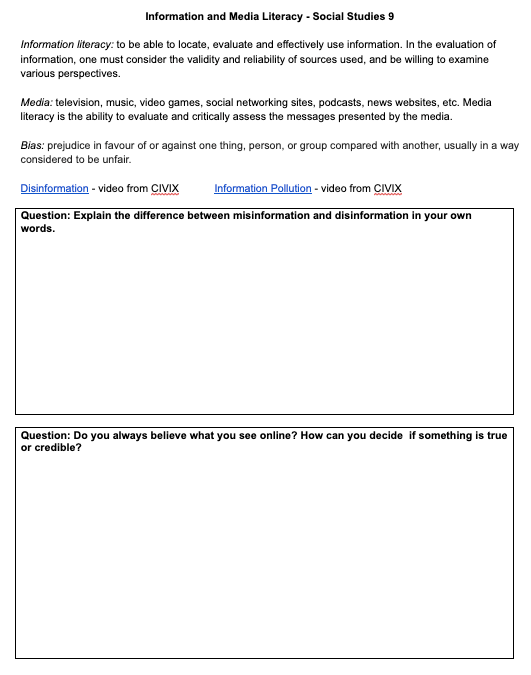

Inspired by the course readings, I did a proper lesson on information and digital literacy with my Social Studies 9 students, whereas in the past it might have been an informal discussion on reliable sources (with me banking on background knowledge of theirs from grade 8). A resource that is both easy-to-use and student-friendly is the Canadian CIVIX, “a non-partisan, national registered charity dedicated to building the skills and habits of active and engaged citizenship among young Canadians. [Their] vision is a strong and inclusive democracy where all young people are ready, willing and able to participate” (CIVIX). Like Clinton noted, “libraries and democracy go hand-in-hand”, and librarians are indeed the guardians of information literacy. CIVIX recognizes this idea that democracy depends on informed citizens, and provides multimodal resources for teachers about how to critically assess media, truth, and bias. It is definitely a source I would keep in my “digital tool kit” as a teacher-librarian, and something I would share widely with humanities teachers.

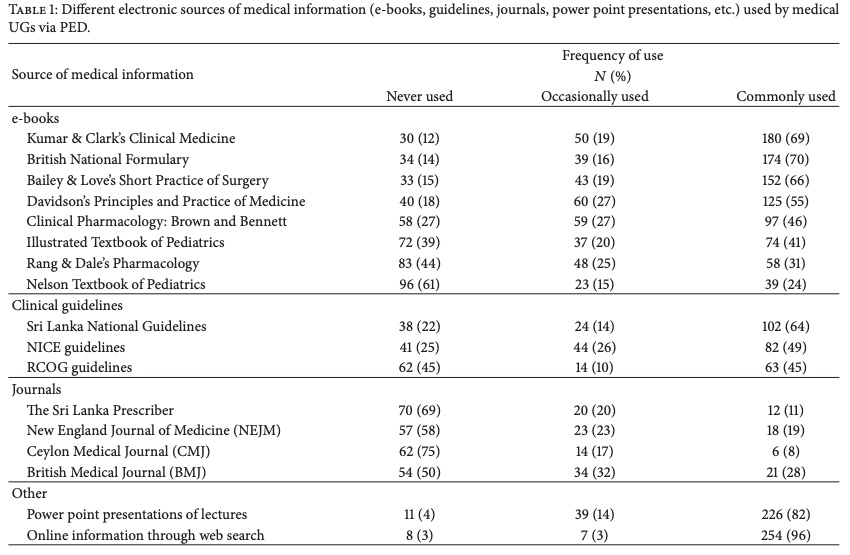

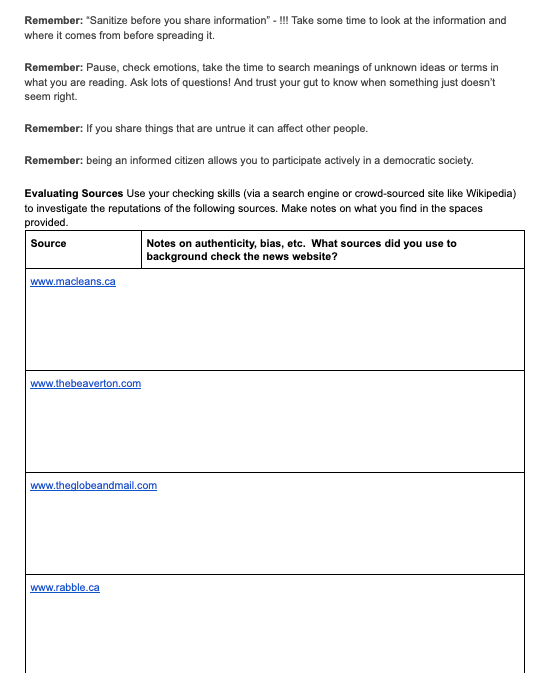

I have used CIVIX in the past to teach grade 9s about government and democracy, as one of CIVIX’s main programs is called “Student Vote”, where they create detailed resources and lesson plans to enfranchise students in times of provincial and federal elections. But I don’t typically spend enough time on digital/media literacy. I discovered that CIVIX has a program called “Ctrl-F: Find the Facts”, with a focus on “Help[ing] students fight information pollution” (CIVIX). This includes videos on disinformation and misinformation, which I used as an introduction to the topic. After a discussion on the differences between them, and also what to look for when checking a factual claim, students then used checklists provided to analyze sources for reliability and bias: Maclean’s, The Globe and Mail, The Beaverton, and Rabble. I introduced them to Media Bias/Fact Check, and they also did some background research on the sources to see what came up.

Finally, we compared Factual vs. Value Claims, using the handouts, Slides, and videos provided by CIVIX. This non-partisan group uses relevant, contemporary information and examples; for instance, they track celebrity claims on social media about the environment, and then demonstrate the research skills to check the claim. Overall, these lessons with the 9s were a curation from the myriad of sources available through CIVIX. You could probably spend weeks on what they provide! I’m grateful for this course for reminding me of the leadership role that teacher-librarians have in digital and information literacy, where T-Ls can provide tools and guidance to teachers, who also have the responsibility to educate students on how to critically assess sources. It was also a good reminder that multimodal resources are the most engaging for students.

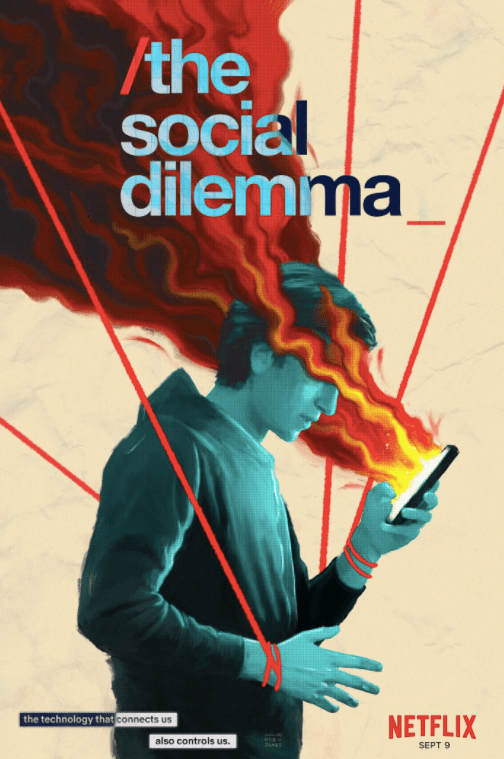

This course has also shown me that in a lot of ways, librarians have to be on the cutting edge of technology, literacy, and understanding of local and global social justice issues. This means being aware of what is going on in popular culture, and how modern technologies and ideas are impacting student life and the way they view themselves in the larger society. Teacher-librarians need to be able to connect on a personal level with students, and if they are completely disconnected from pop culture that makes it more challenging. The documentary film The Social Dilemma was released on Netflix around the same time we were looking at critical literacy and the “8 Science-based strategies for critical thinking”:

The premise of the documentary is that social media companies need to take responsibility for the attention-seeking, data mining they are doing that is affecting people and societies on a subconscious level. In a clip from the documentary, Chamath Palihapitiya, an early senior executive at Facebook explains: “So, we want to psychologically figure out how to manipulate you as fast as possible and then give you back that dopamine hit. We did that brilliantly at Facebook. Instagram has done it. WhatsApp has done it. You know, Snapchat has done it. Twitter has done it” (Scraps from the Loft). Shoshana Zuboff, Professor Emeritus at Harvard Business School, is interviewed in the documentary. She sees the impact of social media on our collective thinking as a threat to democratic society: “These markets [that mine human data] undermine democracy, and they undermine freedom, and they should be outlawed. This is not a radical proposal. There are other markets that we outlaw” (Scraps from the Loft). Showing excerpts from this timely documentary (some students even said their parents asked them to watch it), and hearing these perspectives from experts and engineers in the field of social media (most of whom have removed themselves from the industry for ethical reasons) makes a powerful impact on students.

They see themselves in the dramatic re-enactments of the documentary, and many of the students heed the advice given at the end to turn off notifications, to make choices, to unfollow negative influences, to have a look at how many hours they spend on their devices per day/week, etc. Having done this recently, I can attest to the shock at some of their discoveries on the amount of hours spent on their smartphones. Making students aware of the issues with social media and disinformation engages them to think about how they can change their own habits in order to form their own opinions based on facts and evidence. It contributes to their overall media literacy: “that media is constructed […and that] media have commercial, social, political implications” (MediaSmarts), not only on society as a whole, but also on the students as individuals with their own agency to make decisions about how technology affects their perspectives.

We finished the mini-unit with a personal response, where students were asked to show their critical thinking on the topic:

- What is/are the main message(s) from the documentary The Social Dilemma?

- Do you agree with these messages? Why or why not? Provide at least two examples to prove your point.

- What does information literacy mean to you, or how can you use information literacy to your benefit? (think what we learned about misinformation, disinformation, and checking sources and claims for reliability)

These questions were prefaced with quotes from the interviewees in the film; quotes that showed both the good and evil sides of social technology. This self-reflection is an effective way to remind students of the impact of their daily decision-making, and how social media can have both positive and negative consequences. In the end, information and digital literacy have become central to my humanities teaching after this course. I will continue to make these critical literacies a priority as I move into teacher-librarianship, and will commit to updating resources continually so that they remain relevant and accessible for teens.

How can libraries help students to be themselves?

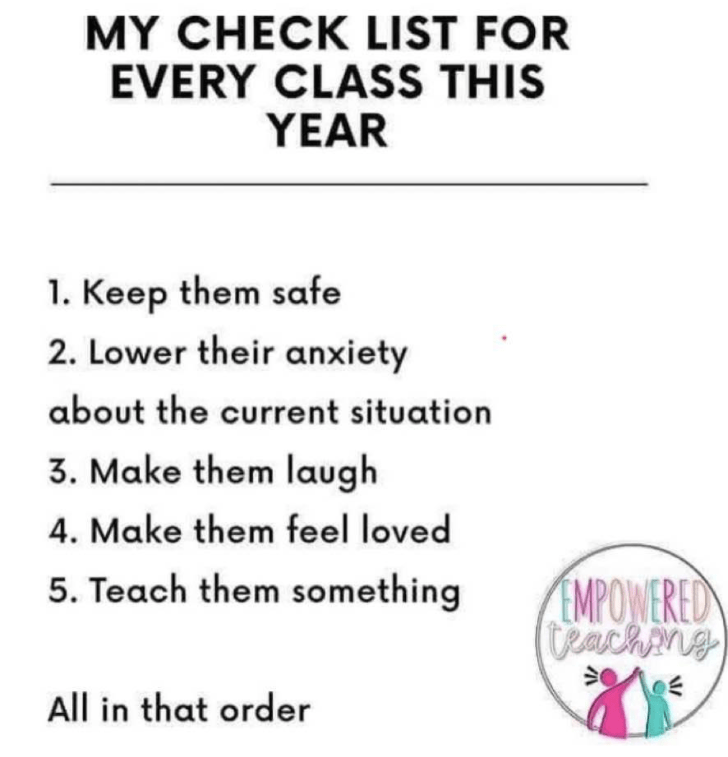

Regardless of your position in the school community, students need positive leadership and role models they can look up to and trust. This is true more than ever in 2020, where leading with trauma-informed practice highlights the need for building relationships and creating safe spaces for students. I’m reminded of the checklist that started appearing in my social media feeds in the spring, as the pandemic led to widespread lockdown. Although I’m having trouble finding the original source, Empowered Teachers, the main message aligns with the learning in this course on the need for care and compassion from teacher-librarians:

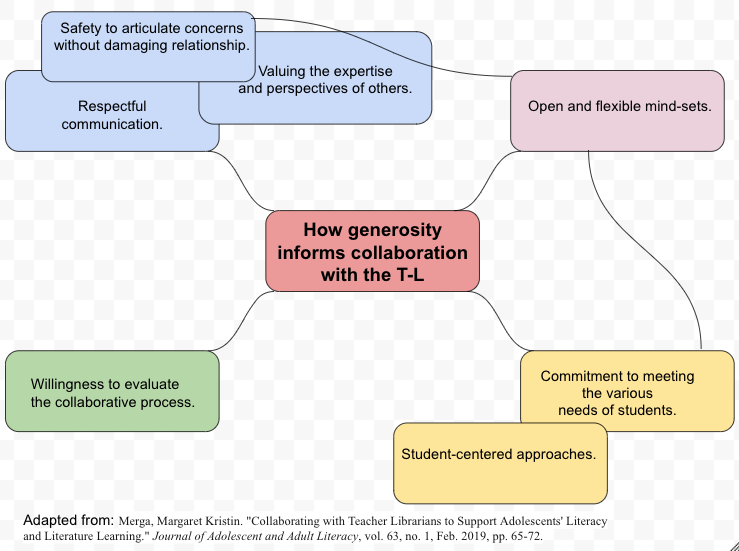

In my reflection on Module 7, I discussed how generosity is at the core of Margaret Merga’s 2019 list for what constitutes good collaboration. All other facets of good collaboration start with understanding and the desire to do what is best for others. While Merga’s article “Collaborating with Teacher Librarians to Support Adolescents’ Literacy and Literature Learning” looks at the relationship between teachers and teacher-librarians, the same concepts apply to the T-L collaborating with and guiding students. Similarly, the checklist from Empowered Teachers focuses on safety, comfort, lightheartedness, and love.

Many resources in this course talked about the library as a non-judgmental community space, where everyone is welcome, and where diverse perspectives are necessary. Hillary Clinton recognizes this as one of the reasons we need libraries more than ever: that these democratic places welcome all walks of life, regardless of social, cultural, or economic background. The librarian is often the first person immigrants come to trust for advice and personal growth opportunities, Clinton explains.

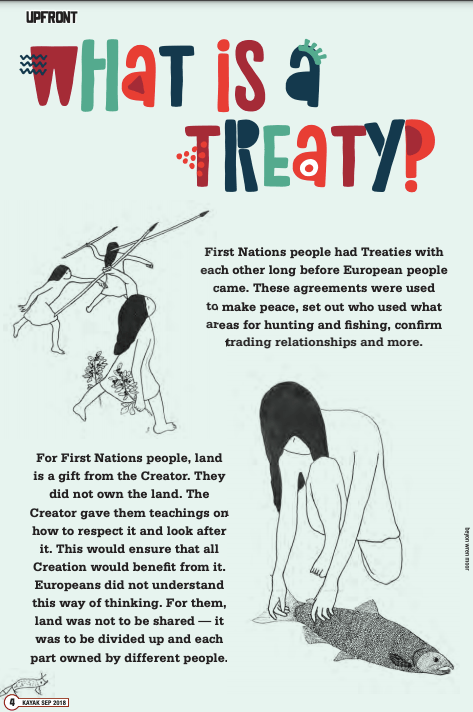

This holds true for the school library, where the T-L might be one of the few adult role models in a student’s life. It is often the place ELL students turn to as they look to improve their literacy skills, trusting the teacher-librarian to find them resources that are at their reading level, but that also respect their interests as teenagers. The LLC should likewise be a safe space for LGBTQ+ voices through the literature and resources available. As noted by a participant in “Demand for Diversity: A Survey of Canadian Readers”, “Diverse books are important so that people feel recognized/validated and so that others from outside that group/identity can have a better understanding of what it’s like to live as a member of that group or with that identity. I think this would help lessen racism and homo/transphobia by increasing visibility” (Booknet Canada). Providing these resources to all students, so that they can become more empathetic towards people who are different than they are, is one of the most significant things we can offer as teacher-librarians. As Rachel Altobelli points out in her article “Creating Space for Agency”, “All students need libraries with books, resources, and stories that mirror who students are and who they might become” (11). This course has also taught me that as educational leaders, we have to be willing to have the difficult conversations about how a lack of empathy in society has led to unfortunate circumstances for BIPOC and LGBTQ+ peoples in our own communities and countries. And how books can help to start these impactful conversations.

Although diversity in literature has always been part of my curriculum throughout my 17 years of teaching, I had never considered fanfic or Makerspaces as engines to promote diversity and agency within the classroom or school library. One idea from Shveta Miller’s blog post on student-created graphic novels has stuck with me throughout these months in the course. She says: “Compelling texts are often ripe with ambiguity. Graphic novels, by their very design, contain “gaps” that readers must fill as they connect one panel to the next. By making connections and drawing conclusions in the gutters—the empty spaces between panels—the reader can help tell a story the writer can’t tell alone” (Miller). These empty or “blank spaces” are a metaphor for the school library; by giving students the blank space to be who they are, or to create what they want, through Makerspaces for example, they are empowered to tell their own stories.

In Module 9, I discussed the “Fellowship of the Fans: Connecting with Teens through the Magic of Fan Fiction” by Anne Ford, who highlights the advantages of fanfic. Writers can “change characters’ genders, ethnicities, sexual orientations, and physical or mental abilities”, contributing to the diversity of voices needed to build empathy in all citizens. Furthermore, “’fan fiction [is] so dear to people [because of] its ability to take characters and adapt them and claim spaces that they’ve previously been denied access to’”, according to Nancy-Anne Davies, a fanfic expert and librarian in Toronto (qtd. in Ford). Populating the blank space of the page, previously unclaimed, gives agency to student writers who may not always see themselves in the literature they encounter. As a teacher-librarian, I would offer the space for these students to fill, with their own ideas, creativity, and perspectives, either through the physical space, the written word, or by offering workshops that breakdown stereotypes (Hunt, Module 9). The hope is that when students feel welcome in the library space, they will feel compelled to create things that matter most to them: “Youth may be empowered within makerspaces to create products that establish and communicate their LGBTQ+ identities” (Moorefield-Lang & Kitzie).

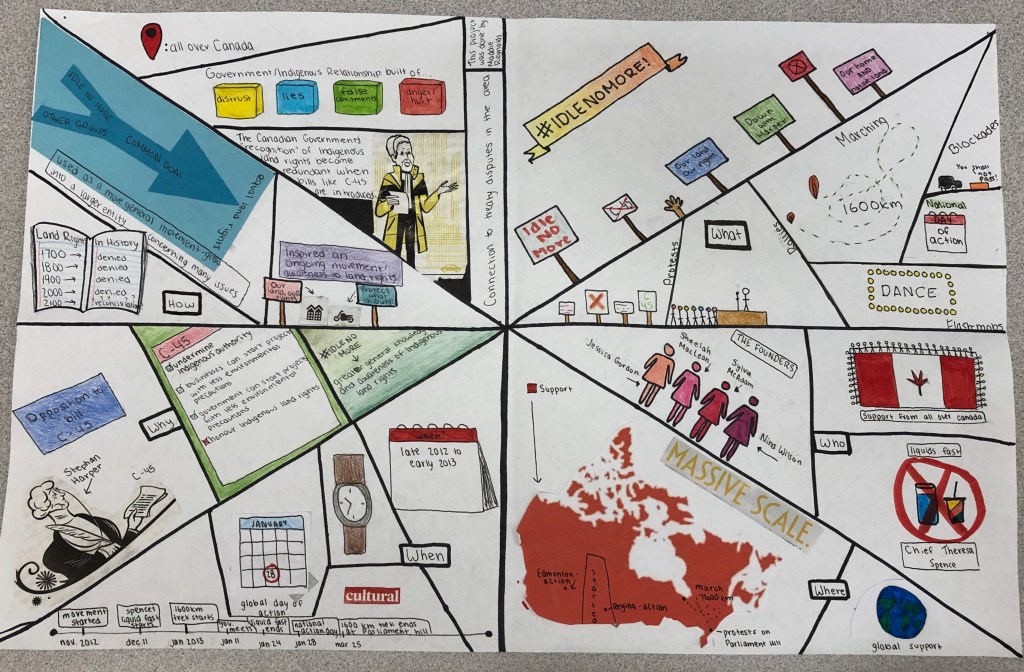

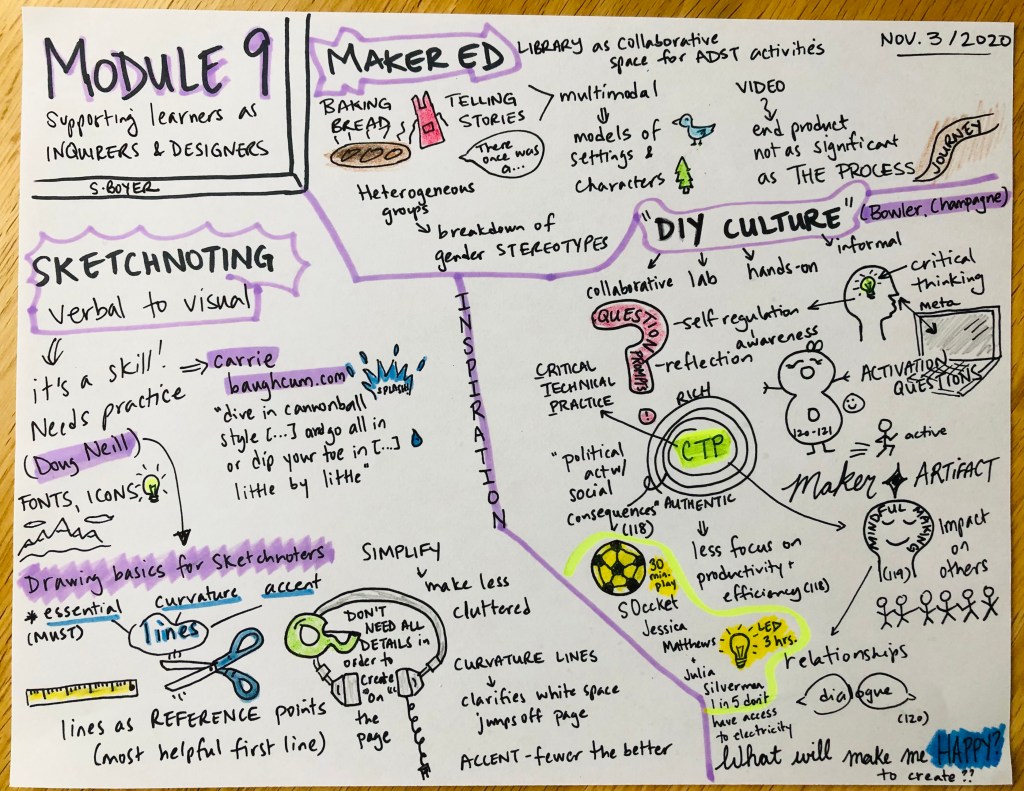

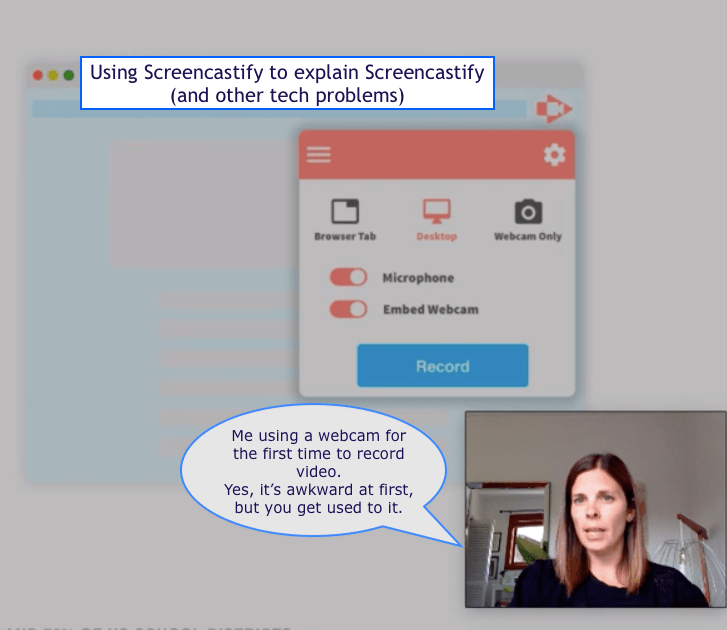

This connects to another major takeaway from the course, which reaffirmed that when students are encouraged to collaborate, be creative, and show their work in multiple modes, specifically visual, great things happen. I am a visual learner who is a doodler by nature, so I tend to give students a lot of opportunities to demonstrate their learning visually. But this typically takes the more formal format of an assignment or group task. And though I have mentioned doodles as a way to help recall information to my classes, I had never actively used it in the classroom as a way to take notes.

Being introduced to the concept of Sketchnotes has had a big impact on my teaching, and is sure to impact my future time as T-L. It not only helped me with recall of my own notes for Module 9, but I witnessed how students could use them to take notes while watching a film or listening to a video lecture. Sketchnotes are more challenging than you think (sketching well while trying to listen closely to a video is tough!), and it is a work-in-progress for me to help students hone the ability to draw their ideas on a topic. One of the positive things I noticed is that they like comparing their drawings, and because what we see in our mind’s eye doesn’t always translate to paper the way we imagine, there is often friendly laughter about what has transpired on the page. People tend to let their guard down when drawing, so it helps improve student relationships when they remove social filters temporarily.

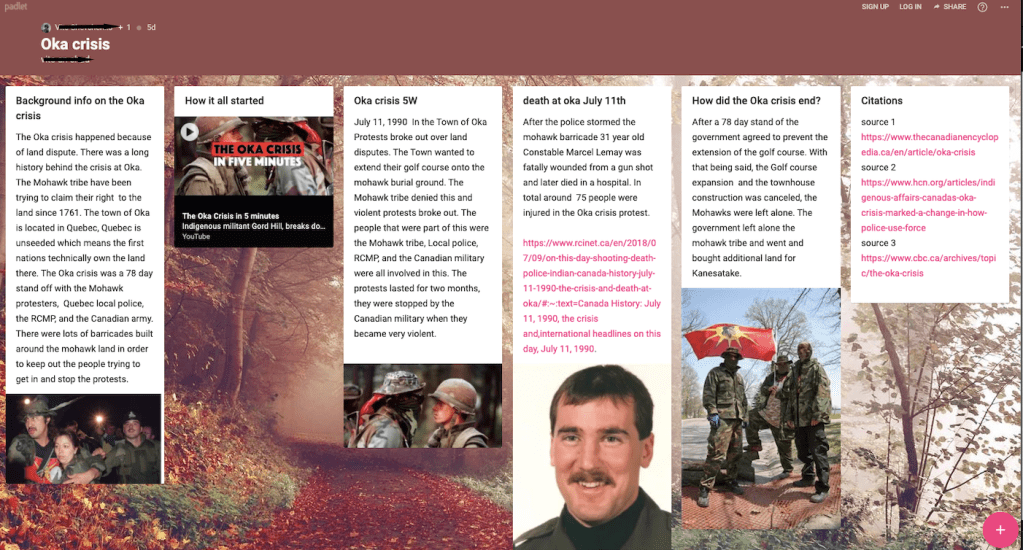

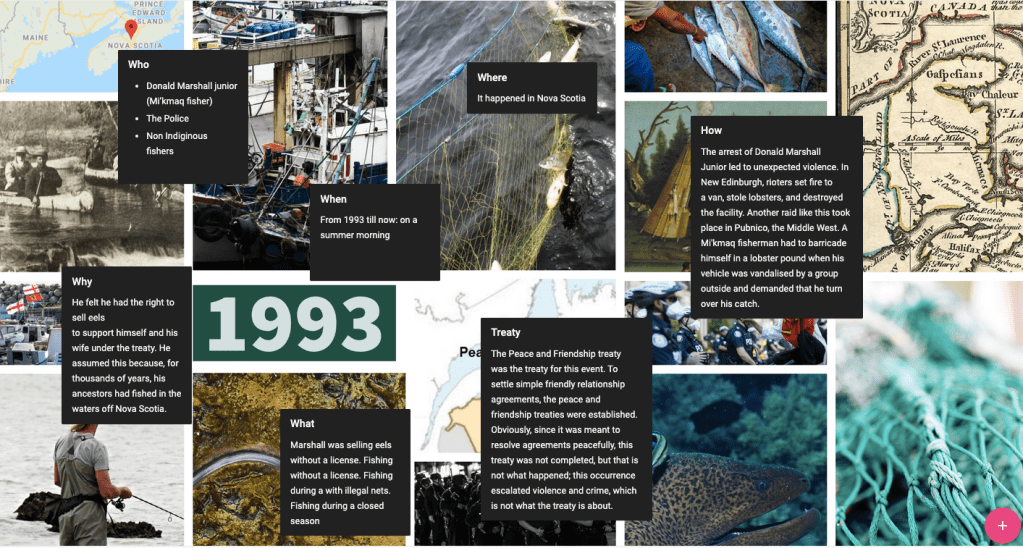

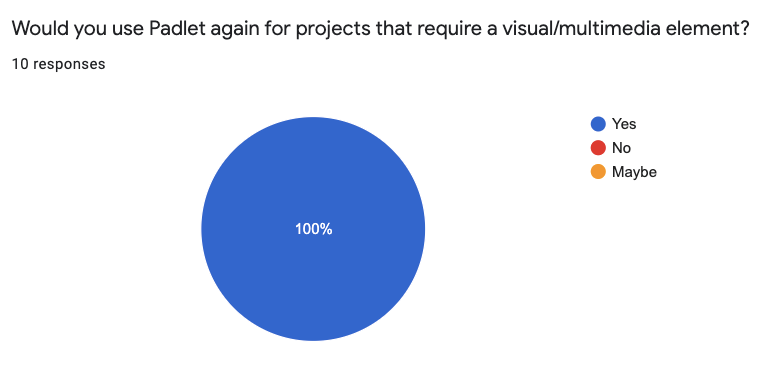

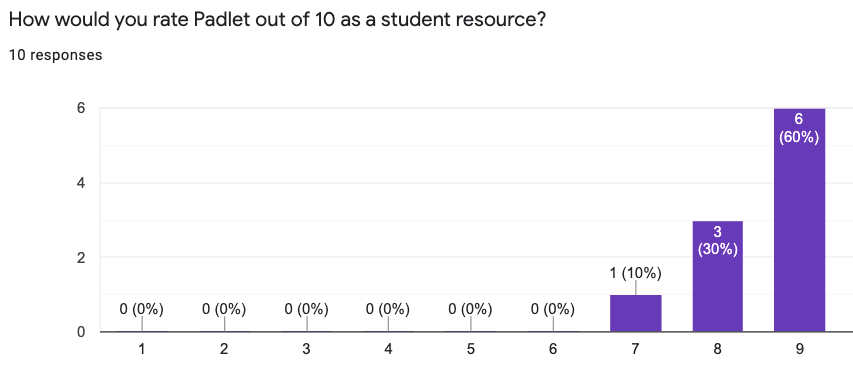

The grade 9s had fun learning the basics of Sketchnoting from the Doug Neill video shared in this course. Moreover, in sharing Sketchnotes between students, there is also a lot of opportunity for encouragement and to notice things about others’ drawings. It’s a small thing that builds community, in the ways outlined by the checklist noted by Empowered Teachers. I similarly enjoyed using Padlet myself and then sharing the resource with students, who successfully created their own digital collages. The student Padlets not only demonstrated strong visual literacy skills, but also critical thinking, and were a great example of multimodality and its usefulness in 21st century learning.

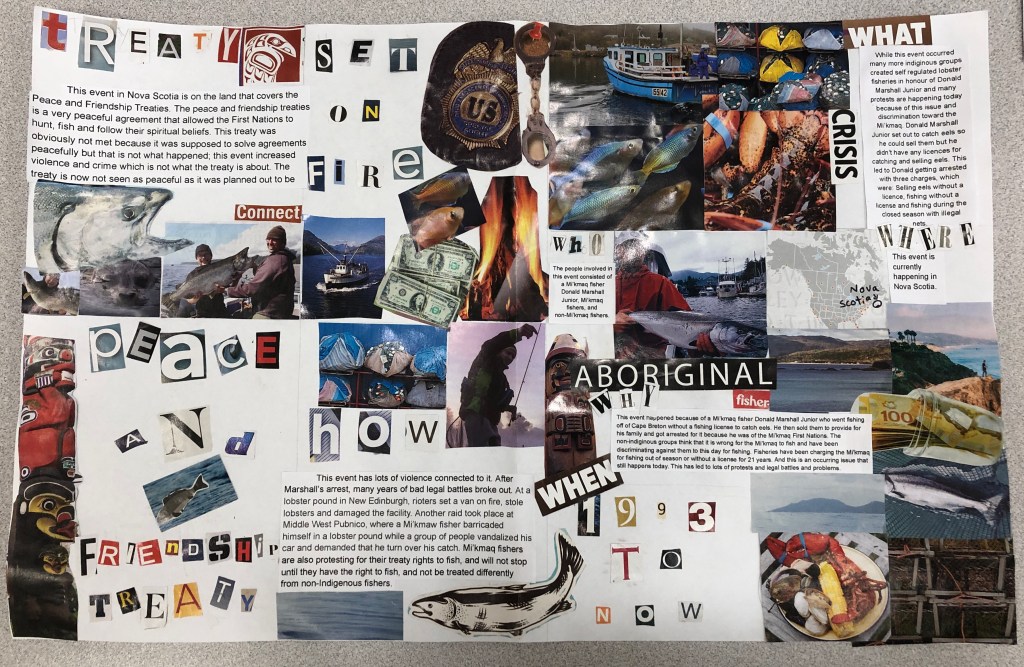

Learning about various student groups that had used multimodal tools to demonstrate learning, such as Crampton’s Critical Digital Projects and Kozak & Schnellert’s “Critical literacy: children as changemakers in their worlds”, reminded me to slow down in the delivery of curriculum content, and focus more on key skills and collaboration between students.

How can libraries help students succeed in all areas of learning?

I think this last question is closely tied to the first two, and that improving information literacy, while empowering students to discover more about themselves through multimodal learning and makerspaces, leads to success in other areas.

Something that surprised me was Stephen Krashen’s findings on the power of books and reading on overall test scores, and that access to a library could balance the negative effects of growing up in poverty. I was also moved by Julie Zammarchi’s video “The Bookmobile” about the mobile library bus that comes to Storm Reyes’ Native American migrant camp and effectively changes her life. Reyes’ is a difficult upbringing full of hard work and poverty, but she finds solace and hope in the bookmobile that arrives in her community. Reading books teaches her “that hope was not just a word. And it gave [her] the courage to leave the camps”. The librarian makes her feel safe and encourages her curiosity, giving her the power to expand her knowledge and eventually empowering her to leave the community behind to pursue a more fulfilling and safe life.

These stories of small comforts that lead to big outcomes is one of our goals as leaders in communities, serving diverse needs and providing encouragement and hope for people who may have lost the ability to understand their own value as contributing to society. As Clinton notes: “For a young person growing up in a small town, the library can be a lifeline, a place to feel supported and to know they’re not alone”. This was Reyes’ experience, and it is one that echoes so many others who are looking for hope, for a mirror to themselves, for a new perspective on the world, for a way to speak up and have an informed opinion that matters. The immense power of reading and librarians is one of my top take-aways from this course, and something I will carry with me as I continue to educate tomorrow’s leaders and “foster the wellbeing of young people” (Merga, 2020).

Works Cited

Altobelli, Rachel. “Creating Space for Agency.” Knowledge Quest, vol. 46, no. 1, Sept.-Oct. 2017, pp. 8-15.

Booknet Staff. Demand for Diversity: A Survey of Canadian Readers. Compiled by BNC Research, Booknet Canada, Apr. 2019.

CIVIX. “Citizenship Education Resources.” CIVIX, 2020, civix.ca/resources/. Accessed 28 Nov. 2020.

Crampton, Anne E., et al. “Meaningful and Expansive: Literacy Learning Through Technology‐Mediated Productions.” Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, vol. 61, no. 5, Mar.-Apr. 2018, pp. 573-76, ila-onlinelibrary-wiley-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/doi/full/10.1002/jaal.723. Accessed 28 Sept. 2020.

Hunt, Christopher. “#MakeryBakery from Module 9: Supporting Learners as Inquirers & Designers.” Edited by Jennifer Delvechhio, LLED 462-63A, University of British Columbia, November 2020.

Ford, Anne. “Fellowship of the Fans: Connecting with Teens through the Magic of Fan Fiction.” American Libraries, American Library Association, 1 Nov. 2016, americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2016/11/01/fellowship-of-the-fans-fan-fiction/. Accessed 10 Nov. 2020.

“Hillary Clinton Full ALA Conference Speech.” YouTube, uploaded by CNN, 27 June 2017, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S8OEAPSFp4c&ab_channel=CNN. Accessed 28 Nov. 2020.

Kozak, Donna and Leyton Schnellert. “Critical literacy: children as changemakers in their worlds.” YouTube, uploaded by UBC Okanagan, 1 Aug. 2018, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yuamzeQX6c4. Accessed 6 Oct. 2020.

Krashen, Stephen. “Dr. Stephen Krashen Defends Libraries at LAUSD Board Meeting.” YouTube, uploaded by LA respresents, 16 Feb. 2014, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JAui0OGfHQY&feature=emb_logo. Accessed 28 Nov. 2020.

Lenters, Kimberly. “Multimodal Becoming: Literacy in and Beyond the Classroom.” The Reading Teacher, vol. 71, no. 6, May-June 2018, pp. 643-49, ila-onlinelibrary-wiley-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/doi/full/10.1002/trtr.1701. Accessed 28 Sept. 2020.

MediaSmarts. “The Intersection of Digital and Media Literacy.” MediaSmarts:

Canada’s Centre for Digital and Media Literacy, MediaSmarts, mediasmarts.ca/

digital-media-literacy/general-information/digital-media-literacy-fundamentals/

intersection-digital-media-literacy. Accessed 29 Nov. 2020.

Merga, Margaret. “Collaborating with Teacher Librarians to Support

Adolescents’ Literacy and Literature Learning.” Journal of Adolescent and

Adult Literacy, vol. 63, no. 1, Feb. 2019, pp. 65-72.

Merga, Margaret. “How Can School Libraries Support Student Wellbeing? Evidence and Implications for Further Research.” Journal of Library Administration, vol. 60, no. 6, July 2020, pp. 660-73, doi:10.1080/01930826.2020.1773718. Accessed 28 Nov. 2020.

Miller, Shveta. “The Surprising Benefits of Student-Created Graphic Novels.” Cult of Pedagogy, 21 July 2019, http://www.cultofpedagogy.com/student-graphic-novels/. Accessed 30 Sept. 2020.

Moorefield-Lang, Heather, and Vanessa Kitzle. “Makerspaces for all: Serving LGBTQ Makers in School Libraries.”Knowledge Quest, vol. 47, no. 1, 09/01/2018, pp. 46-50.

Neill, Doug. “Drawing Basics for Sketchnoters.” YouTube, 21 Sept. 2018, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=po0IEYeLlq4&feature=emb_logo&ab_channel=VerbaltoVisual. Accessed 3 Nov. 2020.

Scraps from the Loft. “The Social Dilemma (2020) – Transcript.” Scraps from the Loft, 3 Oct. 2020, scrapsfromtheloft.com/2020/10/03/the-social-dilemma-movie-transcript/. Accessed 28 Nov. 2020.

The Social Dilemma. Directed by Jeff Orlowski, screenplay by Davis Coombe and Vickie Curtis, Netflix, 2020.

TeachThought Staff. “8 Science-based Strategies for Critical Thinking.” TeachThought: We Grow Teachers, 15 July 2019, http://www.teachthought.com/critical-thinking/8-science-based-strategies-for-critical-thinking. Accessed 28 Nov. 2020.

Zammarchi, Julie. “The Bookmobile.” YouTube, 13 Apr. 2016, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=11OvHcgh-E4&feature=emb_logo&ab_channel=StoryCorps. Accessed 28 Nov. 2020.