Source for image: University of Manitoba

“THE BENTWOOD BOX: CARVED BY COAST SALISH ARTIST LUKE MARSTON, THE TRC BENTWOOD BOX IS A LASTING TRIBUTE TO ALL INDIAN RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL SURVIVORS. THE BOX TRAVELLED WITH THE TRC TO ALL OF ITS OFFICIAL EVENTS” (UM News)

Introduction

The new British Columbia curriculum, among other things, provides specific guidelines and recommendations on incorporating Aboriginal perspectives throughout K-12 and within all subjects. In the “Curriculum Overview” it states that: “[a]chieving this goal will require that the voice of Aboriginal people be heard in all aspects of the education system; the presence of Aboriginal languages, cultures, and histories be increased in provincial curricula; and leadership and informed practice be provided” (“Curriculum Overview”). Within the humanities departments at our school, we have worked hard to improve resources to reflect these important goals. For example, the English department has identified a unique First Peoples text for each grade level, and often collaborates to discuss how to best integrate the First Peoples Principles of Learning throughout the curriculum. These principles were established by FNESC, the First Nations Education Steering Committee, based out of West Vancouver; the principles are meant to be applied throughout all grades and subject areas in BC education.

In addition to reading novels on indigenous topics by indigenous Canadian authors, English Language Arts students must be exposed to accurate background information to support the themes, conflicts, and ideas in the texts. In this way, they can become informed citizens, who “come to understand the influences shaping Canadian society and the unique contribution of First Peoples to our country’s and province’s heritage. Through the study of First Peoples texts and worldviews, students gain awareness of the historical and contemporary contexts of First Peoples, leading to mutual understanding and respect” (“English Language Arts”). Furthermore, one of the main goals for Social Studies students, according to the BC Curriculum, is to have “[a] complete understanding of Canada’s past and present [which] includes developing an understanding of the history and culture of Canada’s Indigenous peoples” (“Social Studies: Goals and Rationale”). Therefore, it is imperative that our school library, as a central gathering place for all humanities students, have the proper reference sources to support this acquisition of knowledge. Given that the curriculum is still quite nascent, it is no surprise that new reference sources are required to bridge this gap.

Positive Change: Indigenous Voices Being Heard in Canada

One of the biggest challenges of previous reference sources and classroom textbooks is that they do not include enough indigenous perspectives or knowledge. Although they may address larger conflicts such as the Indian Act without bias, the majority of these texts are written by people who are not indigenous.

The 21st century has witnessed a positive shift towards working more closely with indigenous scholars and leaders to provide mutually beneficial outcomes on issues that affect all of us, such as land and resource use. This is partly due to the many years of hard work done by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, who presented a number of “Calls to Action” to repair and move beyond the destroyed relationships caused by the residential schools, among other mistreatments by colonial governments. Most recently, British Columbia was the first province in Canada to recognize into law UNDRIP (The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples). This law acknowledges the voices of indigenous peoples, bringing them “to the table for the decisions that will affect them, their families and their territories” (“It’s about a better future…”). According to CBC journalist John Last, in his article titled “What does ‘implementing UNDRIP’ actually mean?”, the UNDRIP “declaration includes articles affirming the right of Indigenous people to create their own education systems, receive restitution for stolen lands, and participate in all decision-making that affects their interests”. All of these actions reflect the long overdue respect needed for indigenous voices in Canada.

“We had 153 years of denial of rights […]. So we’re coming from a period of denial to a period of recognizing that the Aboriginal people … had a way of life.” – Dene National Chief Norman Yakeleya on the implementation of UNDRIP into provincial law (qtd. in Last).

https://declaration.gov.bc.ca/

Providing Great, Accurate Resources for Students to Better their Knowledge on Indigenous Peoples in Canada

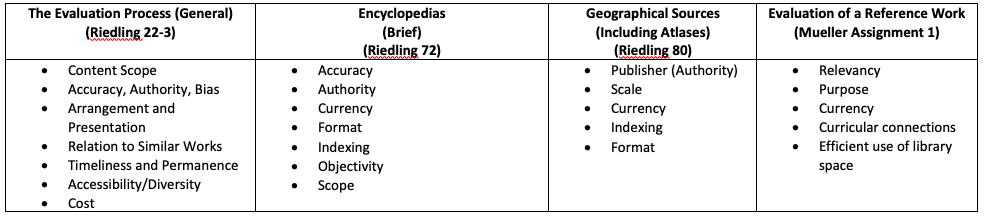

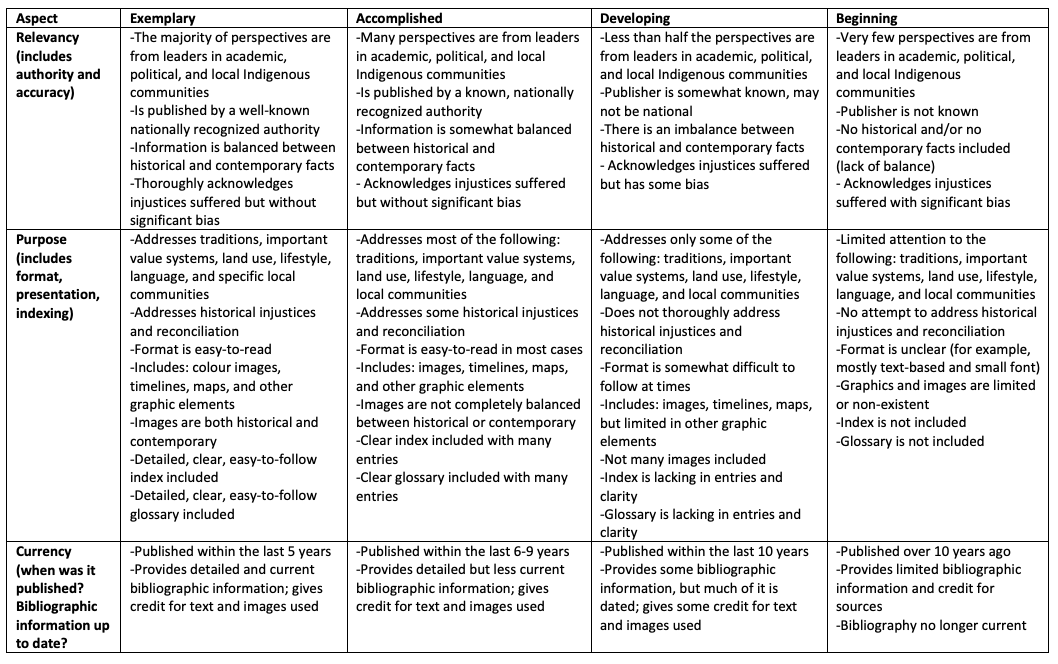

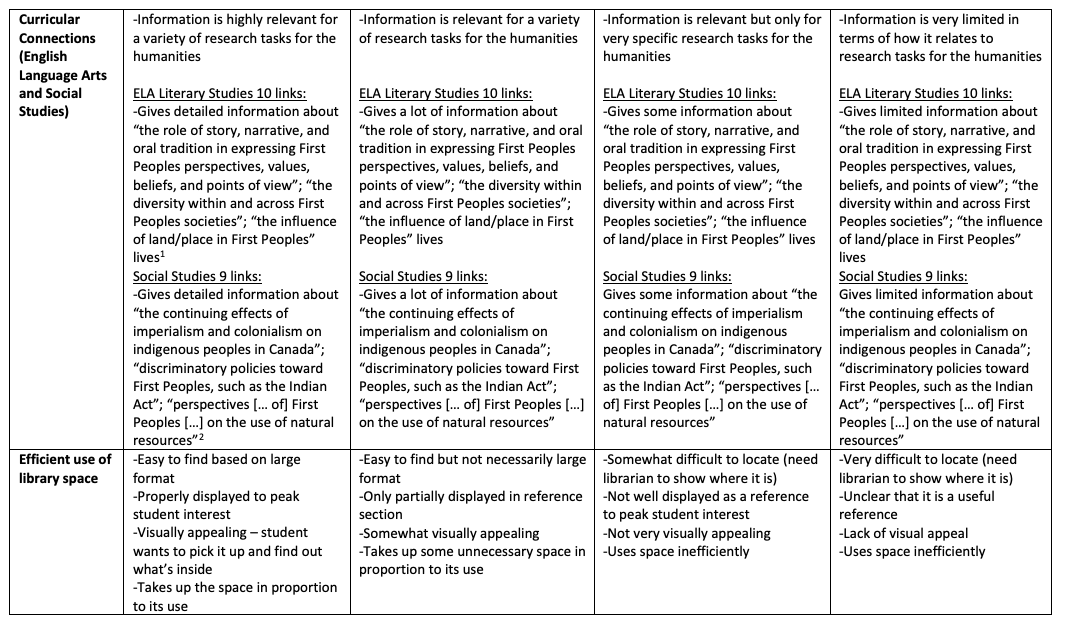

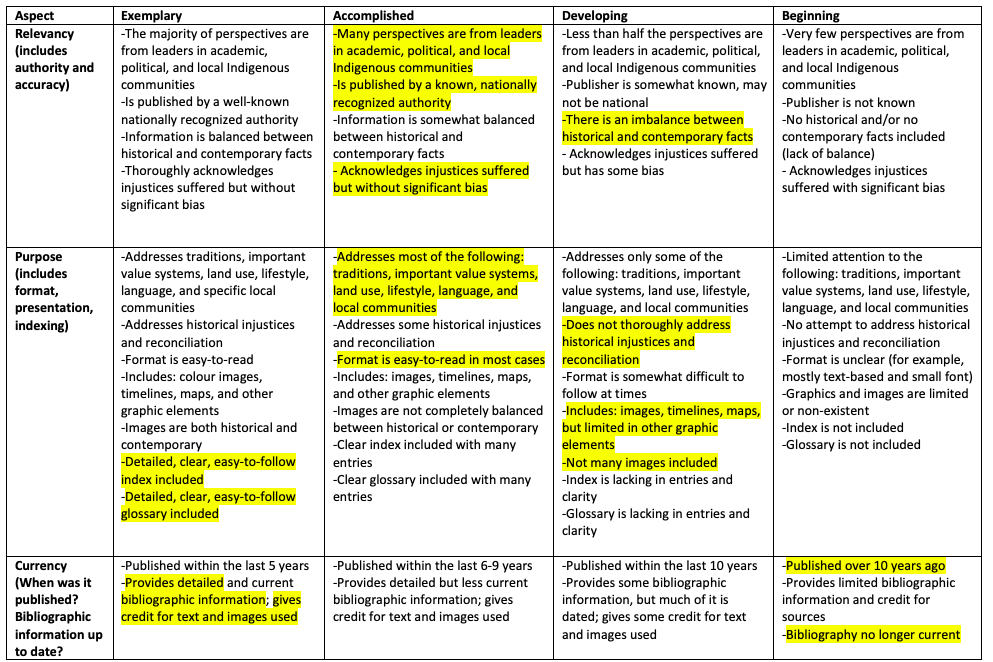

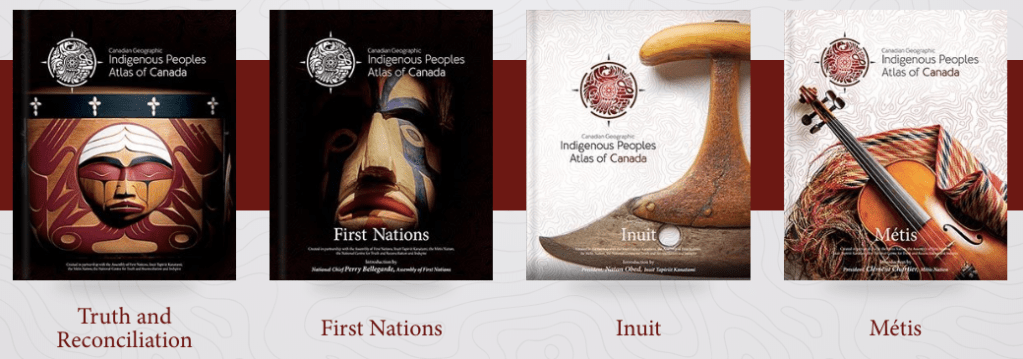

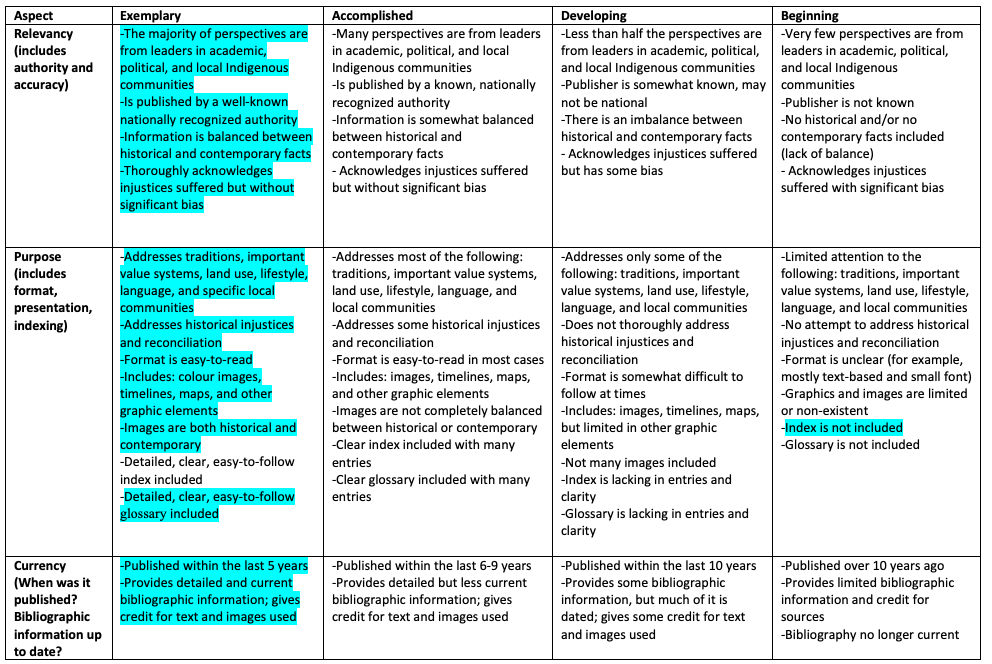

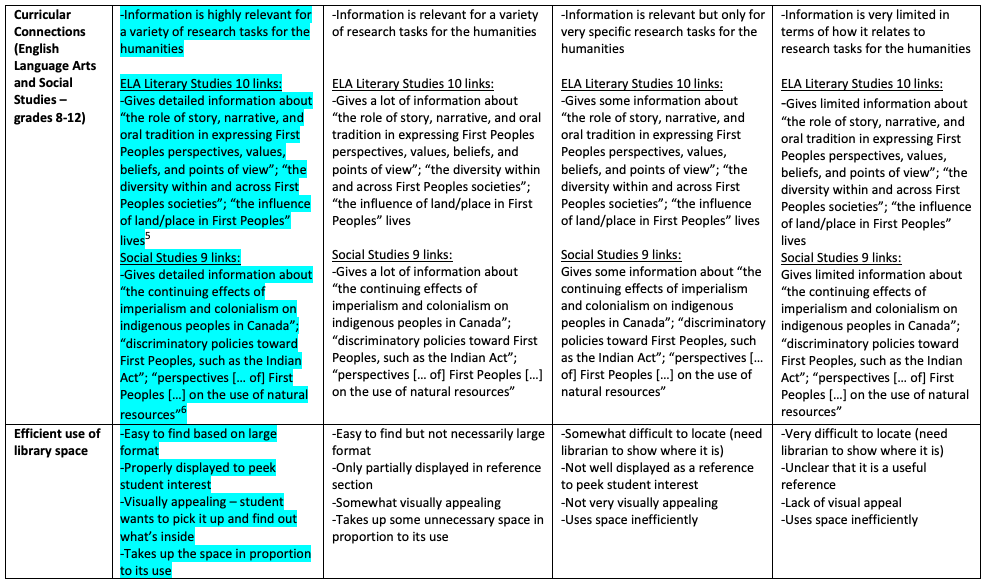

In order to choose a proper reference resource, which can often come at great cost within a typically strained library budget, there are many factors to consider. The chart below outlines four criteria lists for evaluation of a reference source; the first three are from Ann Riedling, author of Reference Skills for the School Librarian; and the last is from Aaron Mueller, UBC Instructor in the LIBE diploma program:

To evaluate the references on indigenous peoples in Canada, I have included aspects from all four lists. This is partly because I am suggesting to replace an encyclopedia collection with a thematic atlas collection. To clarify where curricular connections appear in Riedling’s lists, they would be filed under content, scope, or currency.

You may notice that the rubric I designed to evaluate the sources is heavily weighted on curricular connections. This is because “[m]eeting curriculum needs is a major criterion for placing items in the media center collection” (Riedling 18). I have provided specific links to both the English Language Arts 10 and the Social Studies 9 curricula, since these provide a snapshot of student expectations across two subject areas in the humanities. Moreover, the first aspect “Relevancy” focuses on indigenous leaders as primary contributors, recognizing the significance of these voices in contemporary Canadian learning. With the relatively new developments in curriculum regarding First Peoples, “Currency” makes a big difference in the quality of the resource. In “Purpose”, I wanted to reflect a variety of indigenous topics that are important to understanding perspective and culture. Layout and format are also important factors to a learning resource, since our students are visual learners who are looking for resources that will entice them and keep their attention. Finally, as libraries transition to media centres that address a diverse population using a variety of informational resources, efficient use of space for references is key!

Rubric for a Reference Source: Indigenous Peoples of Canada – History and Contemporary

Sources for Curricular Connections: 1. “Literary Studies 10”. BC’s New Curriculum, Government of British Columbia, 2019. Accessed 5 February 2020. 2. “Social Studies 9”. BC’s New Curriculum, Government of British Columbia, 2019. Accessed 5 February 2020.

Where is the Visual and Local Appeal? Evaluation of an Indigenous Reference Source Currently in our Library

In our school library, we currently have an encyclopedia set titled Native American Tribes, published in 1999, which includes four volumes organized by geographical region:

- Volume 1: Northeast, Southeast

- Volume 2: The Great Basin, Southwest

- Volume 3: Arctic & Subarctic, Great Plains, Plateau

- Volume 4: California, Pacific Northwest

My overall impression of the reference source is that it demonstrates expert research and an extensive bibliography. It is also published by UXL, which is part of the well-known and recognized GALE group. The layout is clear in the sense that it has various subtitles, but the font is somewhat small, and the format is a bit unusual because it is smaller than your standard 8.5×11 page, making it less appealing or easy-to-use. It also does not use any colour images, and the maps are small scale. There is a lot of wasted space in the margins, about two inches of white space on each side, which could have been used to expand font-size or provide definitions. The index is thorough and clear, and it includes a glossary. The front resembles a standard, old-style textbook, which is not very visually appealing to modern high school students.

https://www.amazon.com/U-X-L-Encyclopedia-Native-American-Tribes/dp/0787628425

In addition, Volume 4, which is titled California, Pacific Northwest, only has a small focus on indigenous groups in British Columbia. There are sections on the Tlingit, Haida, and Kwakiutl; however, this leaves out many other significant tribes in British Columbia. The primary purpose of the encyclopedia, according to the title, is to provide information on Native American Tribes. Therefore, it does not provide enough local context to meet curriculum needs in BC. As educators, we know that nomenclature is significant in showing respect to different cultures, and in this case, having a resource that properly uses the term “indigenous” would model correct usage.

This encyclopedia reflects a somewhat outdated style of learning and information gathering, where students might write up a formal report on a particular group. Although this makes sense for elementary learners in some ways, this type of report is rare in our high school.

Here is how this source fared on my evaluation rubric:

Rubric for a Reference Source: Indigenous Peoples of Canada – History and Contemporary

Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes

Time for Some Beauty, Great Layout, and Indigenous Perspectives! Evaluation of an Indigenous Reference Source to Add to our Library

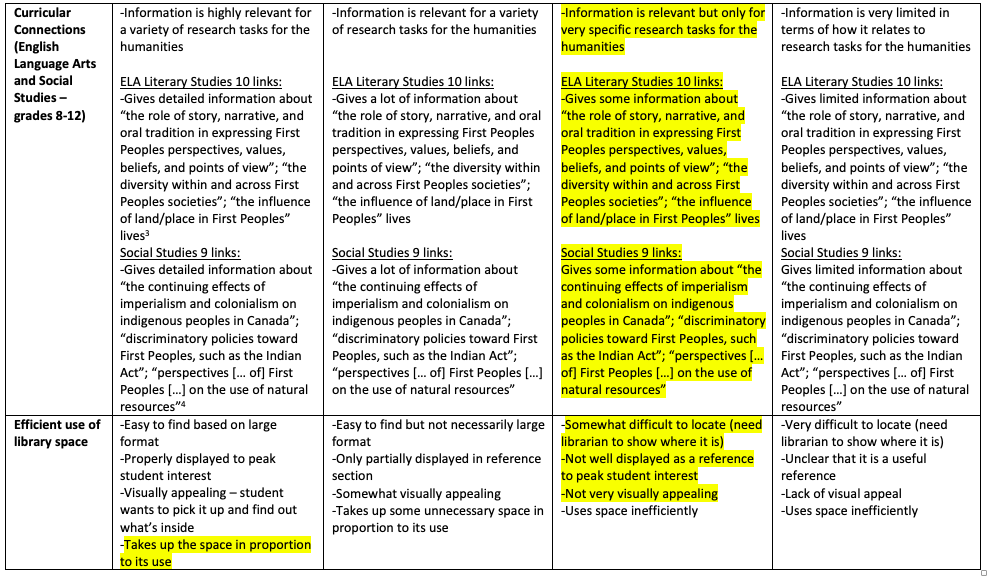

By comparison, the Canadian Geographic Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada provides local context and perspectives from indigenous leaders all over the country. This thematic atlas consists of four volumes:

- Canadian Geographic Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada: Truth and Reconciliation

- Canadian Geographic Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada: First Nations

- Canadian Geographic Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada: Métis

- Canadian Geographic Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada: Inuit

https://indigenouspeoplesatlasofcanada.ca/

The description on the interior title page of each volume states: “Indigenous perspectives, much older than the nation itself, shared through maps, artwork, history and culture”. This sets a clear intention for the resource and reflects the importance of indigenous voices as noted earlier. It also reflects the First Peoples Principles of Learning, which include the idea that “Learning recognizes the role of indigenous knowledge” and ” is embedded in memory, history, and story” (FNESC).

The presentation and quality of the atlases is spectacular; they are large format at 10.7 x 13” and each cover page includes a close-up of indigenous artwork or culturally significant items. Two of the atlases have a black background, and seem shrouded in mystery, while the other two are bright white with contour lines like a map in the background. The items are not fully revealed on the cover, which invites the reader to open the book to find out more. For the most part, each article in the atlas takes place over two pages, side-by-side, making it easy for the reader to follow and make connections between the text and images. Images are in colour when modern, and it includes a number of historical black-and-white photos. There are many other graphics including timelines, flags, symbols, and maps both within articles and several full page maps (included in pp 10-59 in the introductory reference atlas, Truth and Reconciliation).

It was published by The Royal Canadian Geographical Society in 2018, making it both authoritative and current. Furthermore, it states that it was published “in conjunction with” a number of indigenous authorities:

- National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation

- Assembly of First Nations

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami

- Métis National Council

- Indspire

Many of the articles are written by local indigenous authorities, who are given a short biography and photo in the articles. Indeed, according to the description provided on Amazon and Indigo (where one is directed for purchase by Canadian Geographic): “[t]he volumes contain more than 48 pages of reference maps, content from more than 50 Indigenous writers; hundreds of historical and contemporary photographs and a glossary of Indigenous terms, timelines, map of Indigenous languages, and frequently asked questions” (Canadian Geographic). It is also described as “groundbreaking” and “an ambitious and unprecedented project inspired by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action” (Canadian Geographic).

The atlas collection includes a balanced mix of contemporary and historical information on the following topics (and more):

- Language

- Demographics

- Economy

- Environment and Land Use

- Family Structures

- Culture, Arts

- Governance

- Activism and Current Political Issues

- Military Contributions

- Colonialism

- Racism

- Treaties

- Residential schools

Although it does not include an index, which is problematic, the references are easy enough to navigate given the Table of Contents and the short nature of the atlases (they are roughly 70-100 pages each). Perhaps in later editions they will include an index. Expanding its volumes by focusing on particular nations or groupings within the First Nations would also be very useful for detailed research purposes. The publisher would do well to make the spine of each atlas a different colour, because when they are shelved, you cannot easily tell which volume is which. Displaying these atlases upright on reference shelves will help engage students and peak interest.

This is a cost-effective resource because it is so well-priced. Each four-volume set is $99.99, but you can often find them for less. Currently, they are on sale on both Amazon and Indigo for approximately 20% off. I would strongly recommend purchasing a minimum of 4 sets of the atlases to be used as a reference resource in humanities classes, so that several students may have access to the atlases at once.

Here is how this source fared on my evaluation rubric:

Rubric for a Reference Source Indigenous Peoples of Canada – History and Contemporary

Canadian Geographic: Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada, 4 vols.

Conclusion

Overall, replacing the dated and out-of-context Native American Tribes with the modern, thoughtfully constructed and conceived Canadian Geographic Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada will significantly improve the reference section on indigenous peoples at our school. This expert resource reflects the new BC Curriculum rationale, connects to the First Peoples Principles of Learning, and highlights indigenous voices, a significant development for the 21st century in Canada. This source will help our students become ethical citizens, prepared for informed, democratic conversations and decision-making as they become future leaders.

Works Cited

Canadian Geographic Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada. The Royal Canadian Geographical Society, 2018. 4 vols. https://indigenouspeoplesatlasofcanada.ca/

“Curriculum Overview”. BC’s New Curriculum. Government of British Columbia, 2019. Accessed 5 February 2020. https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/overview

“English Language Arts: Goals and Rationale”. BC’s New Curriculum. Government of British Columbia, 2019. Accessed 5 February 2020. https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/english-language-arts/core/goals-and-rationale

FNESC. “First Peoples Principles of Learning” Poster. Accessed 5 February 2020. http://www.fnesc.ca/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/PUB-LFP-POSTER-Principles-of-Learning-First-Peoples-poster-11×17.pdf

“It’s About a Better Future: Indigenous Human Rights Set in B.C. Law”. British Columbia, A New Path Forward. Government of British Columbia. N.d. Accessed 5 February 2020. https://declaration.gov.bc.ca/

Last, John. “What does ‘implementing UNDRIP’ actually mean?” CBC News. November 2, 2019. Accessed 5 February 2020. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/implementing-undrip-bc-nwt-1.5344825

“Literary Studies 10”. BC’s New Curriculum. Government of British Columbia, 2019. Accessed 5 February 2020. https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/english-language-arts/10/literary-studies

Malinowski, Sharon et al. UXL Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. GALE Group, 1999. 4 vols.

Mueller, Aaron. “Assignment 1: Evaluation of a Reference Work”. LIBE-467-63C, University of British Columbia, 2020.

Riedling, Ann Marlow, et al. Reference Skills for the School Librarian: Tools & Tips, Third Edition. Santa Barbara, Linworth, 2013.

“Social Studies 9”. BC’s New Curriculum. Government of British Columbia, 2019. Accessed 5 February 2020. https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/social-studies/9

“Social Studies: Goals and Rationale”. BC’s New Curriculum. Government of British Columbia, 2019. Accessed 5 February 2020. https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/social-studies/core/goals-and-rationale

“Truth and Reconciliation Commission: Reports”. National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, University of Manitoba. 2015. Accessed 5 February 2020. http://nctr.ca/reports.php

University of Manitoba News. “The TRC Bentwood Box”. Artist Luke Marston, Coast Salish. Photo. https://news.umanitoba.ca/honouring-the-sacred-trust/