Source for feature image: “Tips to encourage better teamwork”

For this LLED462 Module, we were posited with a scenario to deconstruct:

A grade 10 student comes into the library weary because he has to submit an intended reading list and goals for the year. The teacher is excited about his/her new syllabus and is making attempts to slowly integrate more choice in reading in combination with the required novels assigned. The only novels he has ever finished, reluctantly, have been the ones that were required reading in class. He dislikes reading and the idea of finishing one novel let alone a pre-determined list for the year is overwhelming. He is thinking of dropping the class.

What do you do/say? How do you help this student? Who do you involve? How do you turn this dilemma into an opportunity?

Response

Establishing a rapport with the student is most important as a teacher-librarian. If he came to me with this concern, I would acknowledge his feelings about it, tell him I was glad he came to see me, and encourage him to work with me, his peers, and his teacher to come up with a list that suits his interests rather than dropping the class.

In his article “Why Our Future Depends on Libraries, Reading and Daydreaming” Neil Gaiman states that “The simplest way to make sure that we raise literate children is to teach them to read, and to show them that reading is a pleasurable activity. And that means, at its simplest, finding books that they enjoy, giving them access to those books, and letting them read them”. From the sounds of it, the grade 10 student has not enjoyed reading in the past, and is reluctant to make reading a part of his daily life through this course.

If the student has only done required reading for courses in the past, it means he doesn’t see the value in reading for pleasure. Donalyn Miller, in Wild Reading, discusses the larger cultural implications of negative stereotypes around reading. She explains “There seems to be a line between reading well enough and reading as a pleasure pursuit […] It’s okay for children to read when asked to perform academic tasks, but if they would rather read than watch TV or play outside, readers become social outliers” (90). I would also add spending time on social media to this list! Similarly, in a study on reading culture at a federal government college in Nigeria, published in 2018, the authors discovered that “students depend chiefly on textbooks, (88.6%), and their teachers (lecture notes) (70.9%) and novels (78.3%) as the most important source of reading material. This finding affirms the reason that students read only to pass examinations”, while other forms of reading are not seen as “important” (Danladi & Soko 32). In my own observations of teenagers, the pull towards technology is rampant; many of them would rather watch YouTube or TikTok videos to fill in leisure time than read.

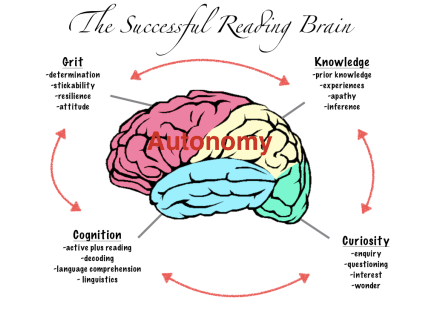

Although a true mindset shift about the power of reading takes time, at least a year according to Stephen Krashen’s research on Sustained Silent Reading (SSR), I would encourage the grade 10 student to think about how reading for pleasure will improve his overall literacy. Reading for enjoyment can improve cognitive skills, and also impact his success in other courses. As Bavishi et al. point out in their study of the impact of reading on older populations, reading books is “a slow immersive process” that leads to deep “cognitive engagement [… which] may explain why vocabulary, reasoning, concentration, and critical thinking skills are improved by exposure to books”. Getting the student to understand the larger picture, that it’s not just about reading for a course to get credit, will hopefully lead to a more open-minded attitude towards reading new and different narratives.

In his discussion of reading for pleasure, Stephen Krashen cites several case studies and histories to highlight the notion that students who engage in SSR have better writing and test scores overall. He states that in a Singapore study of elementary school students, “The students who did reading did better on grammar tests than those who had grammar classes […] I think it happened because the students couldn’t help it. If you read a lot, your knowledge of the conventions of writing, your knowledge of vocabulary, grammar – it’s acquired not learned, it’s subconsciously absorbed, it’s stored deep in your central nervous system, it becomes part of you”. There is a strong correlation between reading for pleasure and overall literacy and growth in other areas.

Furthermore, I would find out what interests the student outside of school, and discuss novels he has liked in the past. What did he like about them? What novels did he dislike and why? At first, I would guide the student to some titles to take home. Ask him to read the first chapter of each book, and see what sticks. Remind him that reading a chapter a day makes you live longer!

I would also speak with the teacher and encourage her to consider making literacy groups where students support one another in their choice of books. Miller and Kelley discuss reading communities at length in their chapter “Wild Readers Share Books and Reading with Other Readers”. They note that although initially they help students find reading material, that “[…] students must learn how to select books for themselves and that this means forging reading relationships with other readers who support and encourage them” (120). This not only helps struggling readers, but also empowers the strong readers to be leaders in their classroom and community (124). The idea is for the peer group to work as a reading team: “For students disinterested in reading, a reading community provides positive reinforcement and nonthreatening reading role models, by forging relationships with classmates who enjoy reading more” (98). In general, this creates a great sense of community in the classroom, where everyone works together; the onus isn’t solely on the teacher or T-L to provide guidance on reading material. It also connects to the Standards of Practice for Canadian School Library Learning Commons where “Students engage in face-to-face […] book clubs based on their interests” and “Students help build a community of readers” as part of Fostering Literacies to Empower Lifelong Learners (17). Curating a reading list is a skill that takes practice and time, so giving the students class time to work on this is essential if it’s part of the overall course learning.

I also think that teenagers typically have a better sense of what their peers will like, or are more willing to hear recommendations from them or social media. Apps like Goodreads offer on-the-spot recommendations for all types of readers; social media apps such as Twitter can offer a wealth of links to great reading resources (Miller and Kelley). As a teacher, you could make the reading list assignment more contemporary and appealing by having students create social media videos with titles of books they’ve read or want to read. In groups or on their own, they could dress up and do a compilation of characters from the novels they’ve read (there’s currently a TikTok challenge where people dress as characters from TV shows or movies! See image below for an example). Working in groups would make this a fun activity to engage students and promote literacy.

Likewise, as the T-L, I would offer to collaborate with the teacher to help students build their lists, and provide them with library time to discover new titles. A quick Google Survey could help with this too – find out what the students are interested in before they arrive at the LLC, and curate some titles for them to get started. Perhaps the teacher could also consider making the reading list a bit more fluid rather than fixed. For example, if a student gets a recommendation from a friend or discovers a new book to add to their list later in the year, they could swap it out for another title.

Overall, communicating to the student that he does not need to face the reading-list-task alone is key. Getting the teacher on board with reading teams and library visits will encourage literacy and growth for all readers, and give students leadership opportunities in the classroom. Aiming for group discussions and fluidity around reading choices is also important. I’ll end with one of my favourite Neil Gaiman metaphors about literacy: “We need our children to get onto the reading ladder: anything that they enjoy reading will move them up, rung by rung, into literacy”. I think one of the first rungs is to make reading for pleasure acceptable, and to make it central to discussions about success in both academics and life.

Works Cited

Canadian Library Association. Leading Learning: Standards of Practice for School Library Learning Commons in Canada. 2014. http://llsop.canadianschoollibraries.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/llsop.pdf. Accessed Sept 15 2020.

Danladi, Diyoshak Rhoda, and Yohanna Rejoice Soko. “The Role of School Libraries in Promoting Reading Culture among Secondary School Students: A Case Study of Federal Government College, Jos.” Library Philosophy & Practice, Oct. 2018, pp. 1–40. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lls&AN=133865535&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Gaiman, Neil. “Neil Gaiman: Why Our Future Depends on Libraries, Reading and Daydreaming.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, http://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/oct/15/neil-gaiman-future-libraries-reading-daydreaming?CMP=twt_gu. Accessed 21 Sept. 2020.

Krashen, Stephen. “The COE Lecture Series Presents: The Power of Reading.” YouTube, uploaded by UGA Mary Frances Early College of Education, 5 Apr. 2012, http://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=2056&v=DSW7gmvDLag&feature=emb_logo&ab_channel=UGAMaryFrancesEarlyCollegeofEducation. Accessed 21 Sept. 2020.

Miller, Donalyn and Susan Kelley. Reading in the Wild : The Book Whisperer’s Keys to Cultivating Lifelong Reading Habits. John Wiley and Sons, 2013. p.88-128.