Featured image source: BizEd

Inquiry Blog Post 4

A discussion of libraries in developing countries is necessarily a discussion of literacy and access to materials.

Books and public libraries have been a refuge for me since I was young; today library time looks a little different, as I most regularly visit with my daughters, aged 4 and 7. I find comfort in knowing the library is a welcoming environment for my girls, where the focus is on literacy and creativity, and where we can wind down after busy days of school and work. In fact, just last night my four-year-old was lamenting a lack of what she calls “mommy-Rosie time” and when we were planning what to do, her first thought was to visit the library (insert heart-bursting emoji here, and also the heartbreak in telling her the library is still closed due to Covid-19).

The ongoing presence of library buildings, with trained librarians, good hours, and great programming was something I took for granted; since libraries have always been “free” to me, books and libraries have factored so centrally in my life. This UBC course inquiry has allowed me to consider the impact of having access to these tools, since millions of people around the world do not. This applies not only to developing countries, but also to low income areas in the developed world. In the UNESCO report written by Mark West and Han Ei Chew titled “Reading in the mobile era: a study of mobile reading in developing countries”, it noted that “According to [researcher Susan B. Neuman], school libraries in poor communities [in the U.S.] are often shuttered, whereas school libraries in middle-income neighbourhoods are generally thriving centres of reading, with one or more full-time librarians” (14). Likewise, across the world in Ecuador, David Risher, founder of Worldreader, discovered that the library he wanted to visit had “a big padlock on the door” and that the woman who worked at the nearby orphanage thought she’d “lost the key” (Neary). The woman explained that it took too long for library resources to arrive by boat, and by the time they got there, students were no longer interested in the content.

The idea of a physical library with print books-in-hand is not feasible when finances are scarce. UNESCO notes that “[e]ven in the twenty-first century, despite enormous advances in publishing, paper books are expensive to design, expensive to print, expensive to distribute, and fragile” (14). This is true regardless of the community in which you live, and library budgets have always been difficult to balance (even digital resources are very expensive to maintain – databases can cost hundreds to thousands of dollars for yearly subscriptions, so if your school district pays for these databases – use them!).

A discussion of libraries in developing countries is necessarily a discussion of literacy and access to materials. The UNESCO report examined the ratio of people to libraries around the world and found that: “In Japan, where 99 percent of people can read and write, there is 1 library for every 47,000 people; in Nigeria, by contrast, the ratio is 1 library to 1,350,000 people (Ajeluorou, 2013)” (14). In other words, a lack of library access leads to higher illiteracy rates. Book ownership is also a luxury that millions of people globally cannot afford: “In Africa a majority of children have never owned a book of their own, and it is not uncommon for ten to twenty students to share a single textbook in school (Books for Africa, n.d.)” (West & Chew 13). These inequities probably do not come as a surprise for many of you, so what can we do about it?

One group, originally based out of New York, but now based out of Australia, has created Library For All, whose mandate is to provide “a globally available free digital library to provide books to communities where inequality, poverty or remoteness are everyday barriers to accessing education”. They “deliver ebooks to students and teachers, even in low bandwidth environments, at a much lower cost than building physical libraries” (Stegman). Although Internet connectivity is not always reliable in developing countries, mobile networks are, so “library content [can be] accessed through mobile phone networks by using low-cost devices such as tablets, mobile phones, and PCs” (Stegman). In fact, according to UNESCO, “Across developing countries, there is evidence of women and men, girls and boys reading multiple books and stories on mobile phones that can be purchased for less than 30 US dollars” (emphasis added, 16). Furthermore, access to mobile technology is more prolific than access to basic sanitation in some cases: “The United Nations estimates that 6 billion people have access to a connected mobile device of some sort, while only 4.5 billion have access to a toilet” (UNESCO). Library For All capitalized on this phenomenon and had a successful pilot program in Haiti in 2013 with e-readers, and is now promoting and improving literacy on 6 continents and in 18 countries. If you are interested in learning more or donating to their global literacy initiative, click here.

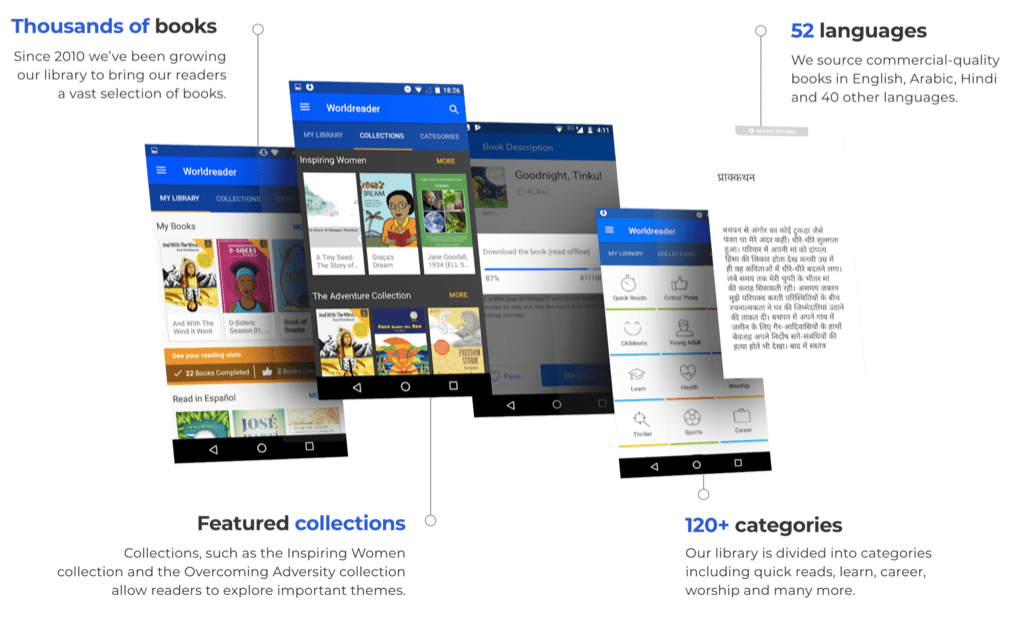

Library For All has an app for accessing content, and is primarily focused on children’s literature for families to enjoy at home, and for educators “to fill resource gaps at school” (Google Play Store). Other applications, such as Worldreader Mobile developed in 2012 by David Risher, offer free books in 52 languages for all ages and tastes. Both apps can be found on the Google Play Store.

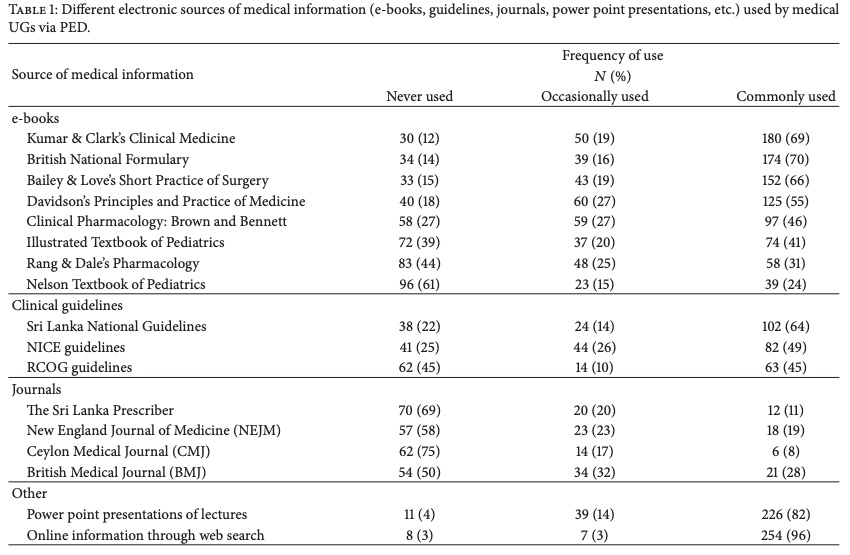

Mobile devices promote reading for pleasure, which is a significant part of improving literacy; they also promote acquisition of curriculum content. For example, in 2014, a Sri Lankan study of medical students who used Portable Electronic Devices (PEDs) found that ““Quick and easy access to reliable and relevant evidence on a PED can improve learning in evidence based medicine and students’ confidence in clinical decision making” (Galappatthy 2). Through these PEDs, students also accessed a number of e-books to guide and support their learning; however, in some cases smartphones were required and these were not always affordable to the students (3). In these cases, the responsibility could be undertaken by the university to provide a loaner device for the duration of course studies for equitability among students. Related to this, many educators and policymakers argue that Internet access, and therefore information access, should be free in a truly democratic society and some countries have moved towards making this possible. In Canada, we have platforms like Shaw Go WiFi hotspots in over 100,000+ locations as a beginner initiative.

Another way digitization and mobile access enhances learning is through Open Education Resources, or OERs. As Mohamed Ally and Mohammed Samaka point out in their article on the advantages of OERs: “Everyone has a right to obtain at least a basic education level so that they can contribute to society and improve their quality of life.[…] Use of mobile technology allows learners to access OER and at the same time participate in learning communities” (15). The OER Commons website is an excellent digital resource that should be accessed and used by educators around the world. Go check it out!

In a previous post, I discussed how a love of reading can translate into success in other areas of work and life. Although many educators tend to shy away from the use of smartphones in our classroom, “[…] mobile devices constitute one tool […] that can help people find good books and, gradually, cultivate a love of reading along with the myriad advantages that portends – educationally, socially and economically” (UNESCO 18). I remember a moment of contemplation when a student asked if they could use Kindle on their phone for silent reading in my grade 10 English class. I hesitated in my conditioning that “phones are bad” in the classroom, but it was a student I trusted to use the time wisely, so I agreed to it. But why hesitate? One of the findings from the UNESCO “Reading in the mobile era” report was “that younger people are more likely to read on a mobile device than older people” (17). Although I don’t think smartphones will replace print books altogether for silent reading (there are still many advantages to printed text), I think they would be a good solution for some of my students.

One of the biggest challenges of silent reading time is “I forgot my book at home”, so there is no consistency in reading as the student picks up a new book each time. Whereas high school students are almost never without their phones in our district. So allowing them to download a book and access it during silent reading time could promote more reading, especially for my low-interest readers. A few things to consider would be: keep them accountable during silent reading time with a guiding question they must answer at the end. This will hopefully help with social media distractions. Similarly, take the time to help students find and choose books. Give them the opportunity to research and download reading apps with free access to books, such as Libby, which allows users to borrow ebooks from their local public libraries (which can be read on a phone or tablet). Libby is new to me, which is embarrassing but also ah-mazing! I will definitely use this as a silent reading option in the future and hope to kindly nudge other teachers in that direction if possible.

In the end, it rests on the individual teacher and their training to work with and share mobile resources to improve literacy. Take Charles from Zimbabwe who states: “‘We live in a remote area where there are no libraries, and the books I have in my own small library are the ones which I have already read. So [Worldreader] is now giving me a chance to choose from a variety of fiction titles’” (West & Chew 40). Here, Charles has taken the initiative to provide more variety to his students, where some teachers may not have the technical knowledge or training to share new resources. Ally and Samaka, in their examination of digital OERs, explained that “It is a simple task giving mobile technology to learners compared to the task of designing and delivering affordable learning materials for access with mobile technology” (16). Can anyone relate to that when they were thrown into remote learning in March 2020 without any additional training?

The authors also noted that technology in developing countries was underutilized in part due to the “lack of affordable learning materials, the lack of motivation of teachers, or the lack of information and communication technology skills of teachers using the devices (Corbeil & Valdés-Corbeil, 2007)” (16). Therefore, one of the ways to promote literacy and reading materials in all educational settings is through professional development, particularly in terms of ICT (a topic I addressed at the personal and professional development level in previous inquiries).

Mobile devices allow free, or very affordable, access to works of literature and other educational resources that help improve literacy and life outcomes for people all over the world. They provide an easy source of information when physical libraries are unavailable, but training and self-regulation around mobile technology is a significant part of using these electronic devices successfully. I hope you will consider donating locally or globally to improving literacy outcomes, or that you will consider trying out mobile devices in a new way in your classroom. Let me know what worked for you!

Works Cited

Ally, Mohamed, and Mohammed Samaka. “Open education resources and mobile technology to narrow the learning divide.” The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, vol. 14, no. 2, June 2013 Accessed 6 Aug. 2020.

Galappatthy, Priyasdarshani, et al. “The ‘e-Generation’: The Technological Usage and Experiences of Medical Students from a Developing Country.” International Journal of Telemedicine and Applications, 24 Aug. 2017, doi:10.1155/2017/6928938. Accessed 6 Aug. 2020.

“Library For All: Digital Library for the World.” Library For All, 2019, libraryforall.org/. Accessed 6 Aug. 2020.

Neary, Lynn. “E-Readers Mark A New Chapter In The Developing World.” NPR, NPR.org, 2 Dec. 2013, http://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2013/12/02/248194408/e-readers-mark-a-new-chapter-in-the-developing-world. Accessed 6 Aug. 2020.

Stegman, Emma. “Library For All’s Push For Literacy In Developing Nations.” Teachthought: we grow teachers, 23 Dec. 2015, http://www.teachthought.com/literacy/library-alls-push-literacy-developing-nations/. Accessed 6 Aug. 2020.

West, Mark, and Han Ei Chew. “Reading in the mobile era: a study of mobile reading in developing countries.” UNESDOC: Digital Library, UNESCO, 2014, unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000227436. Accessed 6 Aug. 2020.

The narrative style of this post and personal connections make it an engaging read. You have shared some excellent ideas and resources here. Libby is ah-mazing! I had our local public librarians come in and show students how to access and use it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Sophie,

I connected with your memory of going to your local library as a child.

As a lonely teenager in the summer I used to take the bus to my local library, take out some books and magazines and go sit under a beautiful big tree on the grass at the park next door. Those are great memories for me.

I recall also, as a high school student on my spare, going to to the public library across the street from my high school to study in order to avoid the distractions at my school library and enjoy a quiet environment. That is one thing I miss about libraries these days; they are not often quiet sanctuaries.

I like how you connected lack of library access for many people in the world to the topic that we were given for this blog post. Like having access to books, and learning that many people in the world have not been given this luxury, not having access to a public library is not something I ever considered before. It is a good point and I like the correlation that you made to literacy and access to a library.

Thank you for the interesting and informing post!

Tara . W.

LikeLike

Hi Sophie! Thanks again for such an enjoyable read! Thank you for the link to Libby: I really appreciate your idea of allowing students or reluctant readers to download an ebook (during silent reading time). Sometimes, out of frustration with the spotty WiFi at our school, I have also allowed students to use their mobile device to edit documents in GoogleDocs or to use them as a French-English dictionary. So far, students have stayed on task, as they need to reach a goal by the end of the class anyway.

I also liked that you mentioned that access to reliable internet was a barrier to accessing reading material on mobile devices. It’s interesting that now it’s becoming more recognized that Internet access is a democratic right. My brother actually lives about an hour outside of Calcutta in India, and although Internet access is very good, it’s actually the frequent electrical outages that get in the way of connectivity!

LikeLike