Introduction

One of the most important components of being a teacher-librarian is collaboration with others, including students, staff, and administration. From providing leadership at staff and department meetings to one-on-one mentorship, supporting the integration of useful reference sources for teachers occurs on many levels.

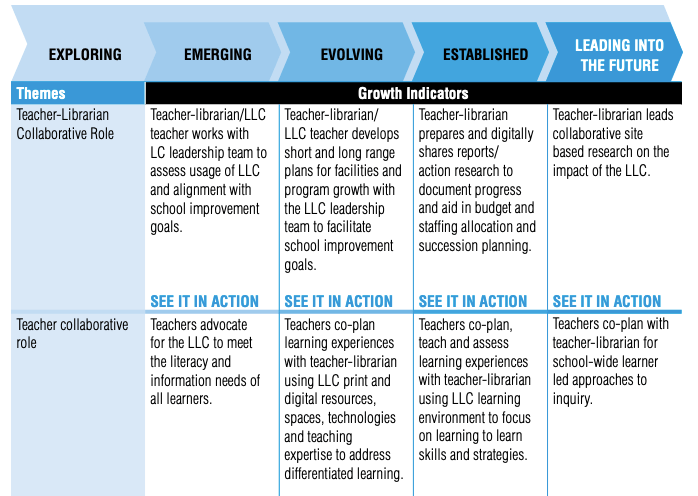

Staff collaboration factors heavily in the foundational rubrics of Leading Learning: Standards of Practice for School Library Learning Commons in Canada. In the standard “Advancing the Learning Community to achieve school goals”, the summary highlights “improved student achievement through the refining of instruction” and that this is achieved in part with “a team to lead the learning commons” (13-14). This team includes staff at all levels within the school and district, and these human resources are the distinguishing factors in each theme for this standard. Specifically, the theme of “Teacher collaborative role” shown below, highlights that “Teachers co-plan learning experiences with [the] teacher-librarian using LLC print and digital resources, spaces, technologies and teaching expertise to address differentiated learning” (CLA 14).

School district guidelines also highlight teamwork as a primary expectation, such as those found in the Greater Victoria School District which states that the teacher-librarian should:

- “participat[e] as a teaching partner in helping teachers address identified learning outcomes through a knowledge of resource-based learning”

- “work[]cooperatively with classroom teachers in order to assist students in developing skills in information retrieval and critical thinking so that they may become informed decision-makers and life-long learners” (Mueller Lesson 6)

However, many teachers are not using library reference services to their advantage; they may choose to either avoid research assignments, or take on the onerous task of independently finding reliable sources. One of our goals as teacher-librarians is to “provide[] leadership and promot[e] strategies for the effective use of a variety of learning resources which support and extend the curriculum” (Mueller Lesson 6). This is more easily achieved when teacher-librarians are approached by teachers themselves seeking guidance, but how can we get the message to others that reference services are open and accessible to help with curriculum outcomes? And how do we understand where the system is lacking?

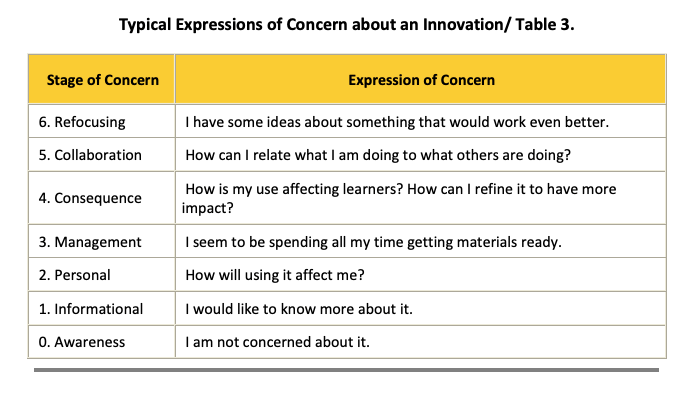

One way to assess the proper integration of new techniques, such as library reference services, is to use the Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CBAM) which was developed in the late 1980s at the University of Texas – Austin, by Shirley Hord and Gene Hall, among others. This model focuses on the personal component of successful innovation, and tracks individual progress through the Stages of Concern. It also emphasizes the importance of guidance and mentorship throughout the process, in order to reach the highest stage: “Refocusing” (Loucks-Horsley 5). Using this model and other research, I will evaluate the use of library references by secondary school teacher, Kevin, through the lens of a research-based senior Social Studies project. I will also address how the humanities department as a whole is using library reference services.

Effective Use of Reference Resources – Kevin

Kevin is a high school teacher with several years’ experience teaching in both Learning Support and Social Studies. He teaches a wide range of courses from grade 10-12, including Social Studies 10 and Human Geography 12. Although Kevin often uses reference sources in his coursework and student assignments, he typically does the time-consuming work of finding reliable sources on his own.

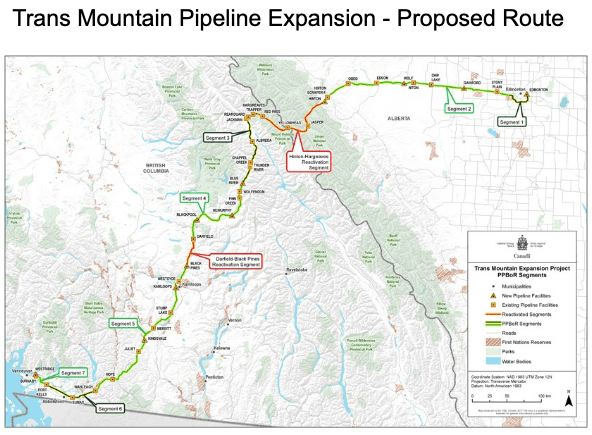

In Kevin’s opinion, this is partly due to the timely nature of his assignments. He recently created a new project for Human Geography 12 on the analysis of the impacts of the Trans Mountain (TMX) Pipeline project in Canada. Since this topic is so extensively covered in news sources that are accessible on the Internet, Kevin found all the resources for this project on his own. However, this accessibility can be hampered by news sources now charging for premium content, and Kevin has the advantage that the Social Studies department budget covered the cost of a group subscription to The Globe and Mail. This brings up the topic of how limits to library budgets might hinder teacher use of the space; without access to a variety of digital resources and subscriptions, research tasks are more challenging and may be avoided.

Kevin admits that finding news articles to support the project was a time-consuming endeavour, but felt proud of the work he had accomplished. Kevin also felt that he had provided a good foundation for evaluating sources by front-loading students with three lessons that gave detailed background information on five different perspectives on the TMX: Geographic, Economic, Environmental, Indigenous and Legal.

I spoke with Kevin while he was in the middle of this assignment, and he expressed positivity about student reactions and interest in the project, and also felt they could be successful in accessing and evaluating sources. However, when I suggested including the teacher-librarian in the scaffolding of the tasks, Kevin was open to the idea of working collaboratively on this assignment in the future, particularly for guiding students in finding reliable sources and creating a proper Works Cited. In this sense, Kevin is functioning in the “Management” and “Consequence” Stages of Concern in the CBAM model (see Table 3 below). He is aware of the time spent on amassing materials, considering student outcomes, and thinking about steps to take next year in order to refine his delivery of the assignment.

The idea is to move Kevin into stage 5, “Collaboration”, where he can work closely with the teacher-librarian, who can provide “mentor[ship so that he] CAN progress and continue to grow” (Loucks-Horsley 7). Through this mentorship, Kevin will have more time to think about stage 6, “Refocusing”. In this last stage, he can work on improving his delivery or assessment of the project, rather than spending the majority of his time finding current or new sources.

Furthermore, working with the teacher-librarian would help support the students, whose main objective in the assignment “Considering the TMX” is to evaluate sources and answer the question: To what extent is the Trans Mountain Expansion in the National Interest of Canada?’. The students were asked to analyze two sources for each perspective, for a total of ten sources, and evaluate relevancy, accuracy, bias, and reliability. Although the teacher provided some background information on how to do this, through modelling and also through this video, this is still a large undertaking and requires a high level of critical thinking and informational literacy skills.

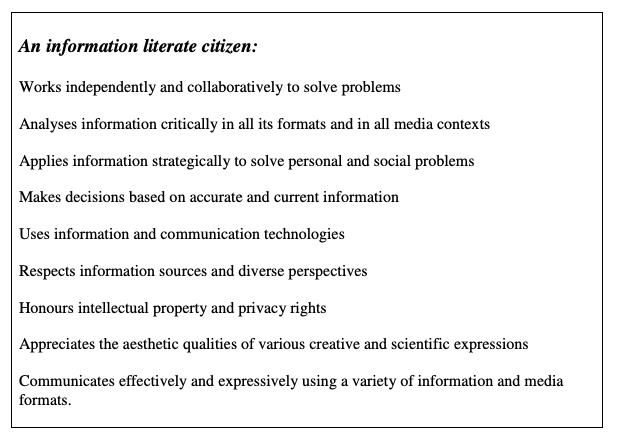

In the chart below from Achieving Information Literacy on what it means to be an information literate citizen, it addresses many of the skills that Kevin is assessing in his assignment. Students must be able to: “[a]nalyse[] information critically in all its formats and in all media contexts”; “[m]ake[] decisions based on accurate and current information”; and “respect[] information sources and diverse perspectives” (5). The role of the teacher-librarian is to create opportunities for students to practice these skills in the larger context of their research question.

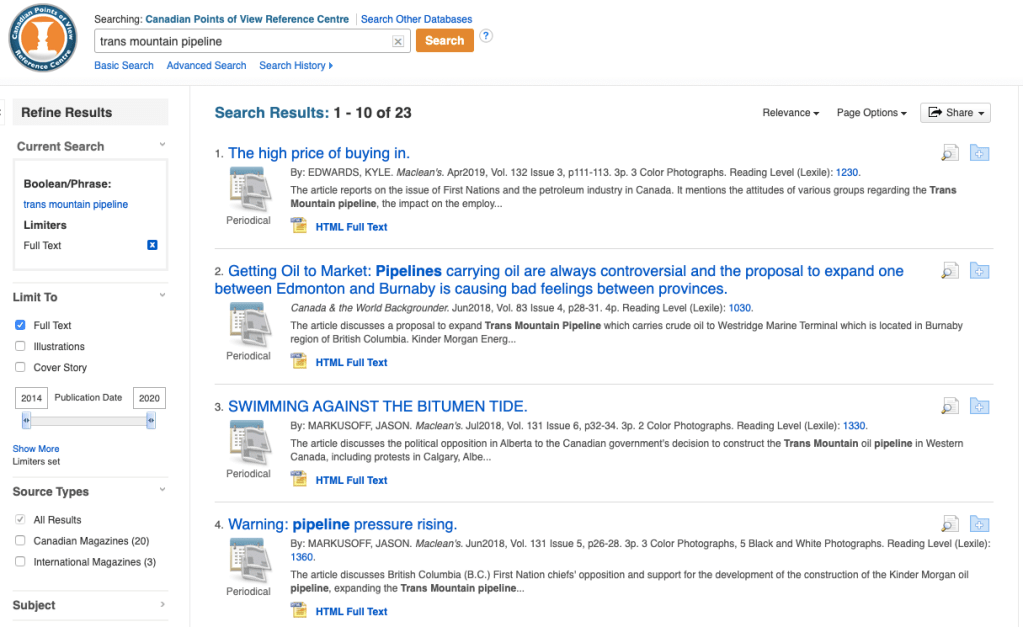

Although Kevin included reliable sources in his initial discussion of the Trans Mountain pipeline, many of his articles came from Global News or other online news sources. By adding some library time at the beginning of the student research process would be beneficial to demonstrate “Information Seeking Strategies”, “Location and Access” of sources, and “Use of Information” from Eisenberg’s and Berkowitz’s Big6 Research Model (Riedling 12). For example, the databases Canadian Points of View, EBSCO, and Gale: Canada in Context include relevant and reliable information on the pipeline topics. If you search “trans mountain pipeline” in Canadian Points of View, 23 hits appear from sources such as Maclean’s magazine, Greenpeace Update, and Windspeaker, offering a variety of different perspectives on this hot button issue.

Ideally, Kevin will establish a strong relationship with the teacher-librarian and seek guidance on other reference-based assignments throughout his teaching. With a good foundation, collaboration becomes more effective, and time-tested strategies can be used again and again to ensure student success.

Results of a Reference Questionnaire for the Humanities

While working on this assignment, I became curious as to how the English/ELL and Social Studies departments at our school viewed library reference services, with particular regards to collaboration with the teacher-librarian. In Lesson 7, it states that one approach to evaluating reference services is to do “a statistical evaluation of the use of reference materials” and to “evaluat[e] the teacher-librarian’s role as the person delivering the reference services” (Mueller). In this vein, I came up with a straightforward questionnaire to gauge staff use of library time at our school:

I made both paper and electronic (Google Forms) versions of the questionnaire, each with its own advantages. Interacting with teachers by providing a paper version gave me the chance to explain my reasoning and led to informal conversations about the use of library time; since building relationships and good communication are such a significant part of the teacher-librarian role (Riedling 102), this exercise was beneficial. Meanwhile, the electronic version allowed me to reach teachers I don’t see regularly due to work or location hours.

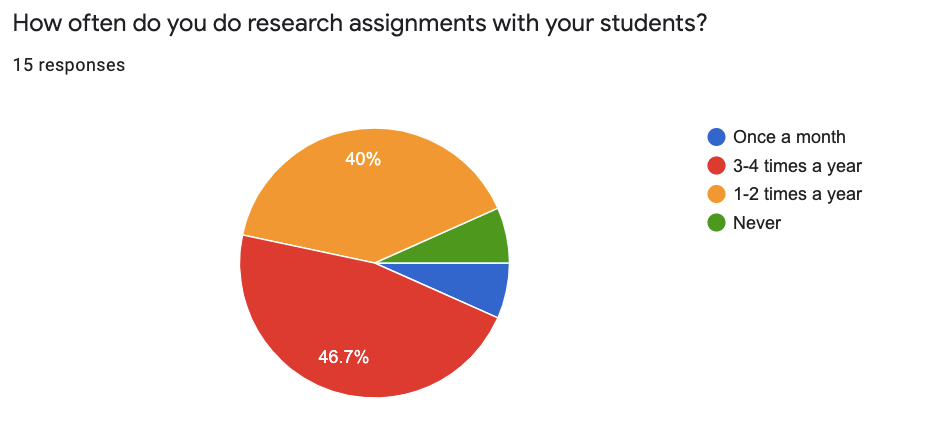

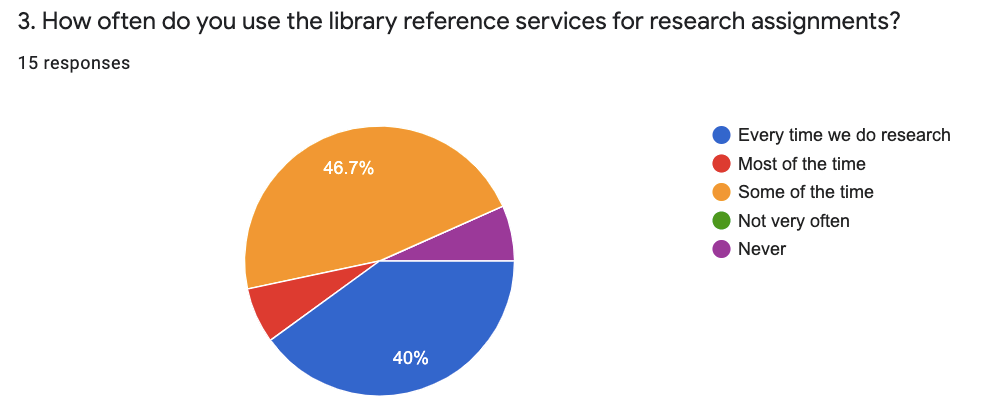

Between the two departments, I was able to get 15 responses. Generally speaking, the Social Studies teachers use library reference services more often than the English/ELL department, which is to be expected based on curriculum outcomes and expectations; Social Studies use the library 3-4 times a year versus 1-2 times for English/ELL. It was encouraging to see that 40% of teachers use the library “Every time” they do research, while 46.7% used it “Most of the time”.

For question 4 “What challenges do you face when coming up with lessons or projects that include using reference sources?”, the majority of teachers were concerned about plagiarism, reliable sources, and helping students with MLA formatting and citations. For this topic, I believe that many teachers are in Stages 4 and 5 of CBAM, “Consequence” and “Collaboration”, since they recognize that seeking out support from the teacher-librarian will help with many of these issues.

When it came to question 5 about collaborating more directly with the teacher-librarian, many teachers in the Social Studies department checked all boxes on the survey, while some English teachers checked off all boxes except “Help with planning research tasks and assessment”. Only 40% of the total teachers surveyed said they could see themselves co-planning an assignment with the teacher-librarian. Technology use, such as databases, Pathways, Noodle Tools, and search tools for reliable sources were seen as more significantly useful to teachers.

Although 40% is a decent percentage and demonstrates that the teacher-librarian role is seen as collaborative to many staff members, it means that 60% are in the “Informational” or “Personal” stages of CBAM. In these stages, they may not be aware of how to best utilize the teacher-librarian as a resource for planning; or perhaps they are concerned about how it could affect their own planning and control over an assignment. Indeed, 33.3% of teachers said that a “Lack of personal time in planning” is a challenge to them using library reference services for projects. If I were to run a similar survey in the future, I would ask a more direct question about co-planning and ask for a brief written response on how staff views collaboration with teacher-librarians.

Conclusion

Overall, teachers tend to be open about using library time for reference services, and are aware of the challenges that come with student access to a vast amount of electronic information. They see the teacher-librarian as a support in finding and modelling reliable sources and citations, and many are interested in learning more about databases and Pathways; this thinking reflects the higher Stages, 4 and 5, of the CBAM. However, when it comes to co-planning, one of the many role descriptions based on library standards in districts and nation-wide for teacher-librarians, not all staff are ready to participate, putting them in Stages 1 and 2 of the CBAM. Through education and promotion of the teacher-librarian role in the school, hopefully more teachers will be open to co-planning in the future.

Works Cited

Asselin, Marlene et al. Achieving Information Literacy: Standards for School Library Programs in Canada. Canadian Association for School Libraries, 2006. http://accessola2.com/SLIC-Site/slic/ail110217.pdf

“Both sides trying to sway opinion on Teck Frontier Mine”. Global National, Global News, January 22, 2020. https://globalnews.ca/video/6449562/both-sides-trying-to-sway-opinion-on-teck-frontier-mine Accessed 3 March 2020.

CLA. Leading Learning: Standards of Practice for School Library Learning Commons in Canada. Canadian Library Association, 2014.

“Detailed Route maps for Trans Mountain Expansion Project review”. Canada Energy Regulator, Government of Canada, Jan. 8, 2020. Accessed 2 March 2020. https://www.cer-rec.gc.ca/pplctnflng/mjrpp/trnsmntnxpnsn/mps-eng.html

Loucks-Horsley, Susan. “The Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CBAM): A Model for Change in Individuals”. National Standards and the Science Curriculum (ed. Rodger Bybee). Iowa, Kendall/Hunt Publishing, 1996. https://s3.wp.wsu.edu/uploads/sites/731/2015/07/CBAM-explanation.pdf Accessed 27 February 2020.

“Media Skills: Crash Course Media Literacy #11”. Crash Course. May 8, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Be-A-sCIMpg&t=274s Accessed 3 March 2020.

Mueller, Aaron. “Lesson 6: Managing the Reference Collection”. LIBE-467-63C, University of British Columbia, 2020.

Mueller, Aaron. “Lesson 7: Evaluating Reference Services”. LIBE-467-63C, University of British Columbia, 2020.

Riedling, Ann Marlow, et al. Reference Skills for the School Librarian: Tools & Tips, Third Edition. Santa Barbara, Linworth, 2013.

“Trans Mountain Pipeline” Basic Search. Canadian Points of View Reference Centre. EBSCO Industries, 2020.